Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

In the previous issue of the newsletter, we talked about four existential threats to our American democracy:

American oligarchs: the rise of the ultra-wealthy, who are empowered by the effectively unlimited funds at their disposal

Corporate wealth and power: highly-profitable corporations that can spend unlimited funds on political campaigns

Economic resentment: anger and resentment among people who have been left behind in the country’s economic growth

Campaign finance laws: defanged campaign finance laws that allow individuals and corporations to use their wealth both stealthily and effectively to advance their political agenda

Threats 1 and 3 arise from our lopsided distribution of wealth, which helps the wealthy get wealthier and makes it more difficult for the poor to get ahead.

Our topic here is how our tax system redistributes wealth.

Some politicians are fond of saying or implying that the federal government takes our hard-earned dollars and give them to the poor. Remember what then-presidential-candidate Mitt Romney told a gathering of wealthy donors, referring to the 47% of Americans who pay no federal income tax:

"All right, there are 47 percent who are with him [Obama], who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it. That that's an entitlement.”

Romney’s 47% number was correct, but as Ezra Klein explained, his implication that many Americans are getting a free lunch was not.

And, remember Paul Ryan? He was fond of dividing us into “makers” — job creators who pay federal income taxes — and “takers” — people who don’t owe federal income taxes because they don’t have much income. While Ryan eventually walked back his rhetoric, he continued for the rest of his political life to pursue policies based on the idea that the wealthy pay too much and the poor should get less help.

Conservative thinker, pundit, and journalist Ramesh Ponnuru, writing in The National Review, explains why this idea that those who don’t pay income tax are “takers” is both factually wrong and counter to conservative thinking.

I’m going to explain that, the “takers” messaging notwithstanding, the wealthy, not the poor, are the big beneficiaries of government largess, delivered as tax breaks. Let’s begin the story now.

Some Taxing Stories

Alice the Investor & Bob the Consultant

Let me tell you a (fictional) story about Alice and Bob.

Alice bought 1,000 shares of Amazon stock on January 2, 2017 for $795.99 per share, a total of $795,990. She sold it five years later on December 27, 2021 for $3,372.89 per share, a total of $3,372,890. Alice’s investment has earned her $2,576,900 over five years.

For those same five years, Bob worked as a self-employed consultant earning $515,380 per year, which totals to — surprise — $2,576,900.

Who is better off, Alice or Bob? Let’s compute their federal taxes1.

Alice had no income to report from 2017 to 2020 because long-term (held more than a year) capital gains are taxed only when the asset is sold. In 2021, her taxes were2:

Alice had $1,999,550 in after-tax profit.

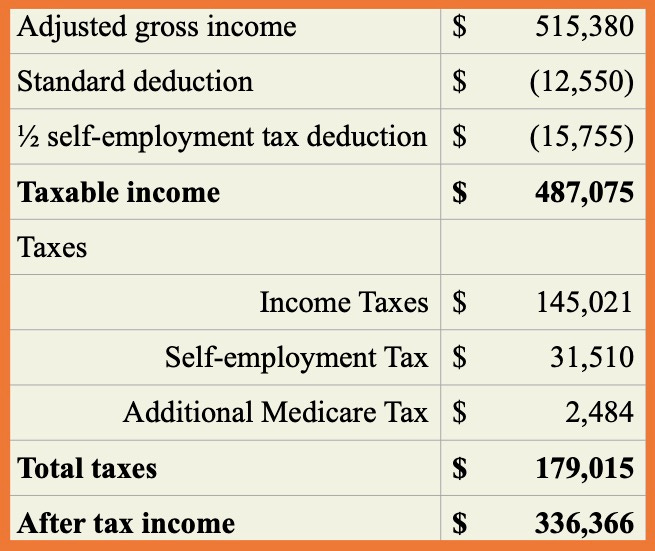

Bob had to pay taxes on his income annually:

After five years, Bob had $1,681,828.

Despite Alice’s and Bob’s equal earnings, Bob’s five years of work got him only 84% of Alice’s five years of investing.

Our tax system taxes long-term capital gains at a lower rate than ordinary income3.

As we’ll see later, this example is but the tip of the iceberg in the benefit of preferential treatment of long-term capital gains.

Alice Dies Before Selling Her Stock

Now let’s change the story: Alice dies on December 27, 2021 before selling her Amazon stock. Her daughter Sally inherits the stock and decides to sell it on January 4, 2022 at a price of $3,387.14. How much tax will Alice’s daughter pay on the profit from Alice’s stock?

The tax code allows a “step-up in basis” on inherited assets, which means that instead of computing Sally’s profit based on Alice’s original purchase price, Sally’s profit is only the change in the stock’s value from the fair market value (FMV) on the day Alice died. FMV is the average of the highest and lowest price on that day, which in this case is $3,421.58.

So, for the purposes of computing taxes on the capital gain, Sally’s per share profit selling her mother’s Amazon stock is $3,387.14 - 3,421.58, which is a loss. Neither Alice’s estate nor Sally owe any capital gains taxes on the more than $2.5 million profit Alice made on her investment! Indeed, depending on the rest of her tax situation, Sally may even be able to claim a loss on the stock she inherited.

Sweet.

Our tax system allows capital gains to be passed to heirs untaxed.

Alice Remembers Her Alma Mater

Let’s change the story again. This time, Alice is both healthy and feeling generous. She decides to endow the Alice Generous Person scholarship at her alma mater. She donates her (unsold) Amazon stock to her alma mater on December 27, 2001. The IRS considers this to be a charitable contribution of a long-term (more than a year) appreciated asset. Alice pays no taxes on her more than $2.5 million gain. Alice also can deduct from her income as a charitable contribution the full $3.4 million fair market value of the stock4.

Our tax system allows long-term appreciated assets to be donated with the capital gains untaxed and the donor can deduct the full value of the donation, including the untaxed gain.

Alice Loves Art

One more time — let’s change the story. Alice is an art lover and wants to build a collection for her enjoyment. So, she creates (and controls) a private, non-profit foundation to hold her collection. She’ll have to convince the IRS that there’s some public benefit to her foundation — maybe they’ll host schoolchildren for occasional visits. Then, she donates that Amazon stock to the foundation and gets all of the tax benefits as in the alma mater example. The foundation buys the art she wants, does whatever bit of public benefit she promised and now she has essentially a private collection largely paid for by tax benefits. See Writing Off the Warhol Next Door for a real-life story.

Alice Becomes a Philanthropist

Alice wants to be recognized as a philanthropist in her community. So, she donates her Amazon stock to a donor-advised fund5 to establish the Alice Generous Person Charitable Fund. Donor-advised funds, which are recognized by the IRS as charities, invest a donor’s funds and allow the donor to “recommend6” contributions to specific charities. As in the previous two examples, Alice can deduct the full value of her Amazon stock and no capital gains tax is ever paid.

The donor-advised fund invests Alice’s donations according to her instructions (usually, the donor can choose from a handful of mutual funds) and tracks the value of the Alice Generous Person Charitable Fund. Whatever gains the Charitable Fund makes are forever untaxed. When Alice wants to make a charitable contribution, she “recommends” it to the fund, which makes the donation.

Or, Alice can just keep all of that money invested in the fund. There’s no requirement that it be distributed to actual charities on any timetable.

Besides fictional Alice, real-life Elon Musk and other billionaires7 are reputed to use donor-advised funds. Musk, for example, announced a $5.7B charitable donation, but no charity has announced receiving any money from him, leading to speculation that the money is parked in a donor-advised fund.

Alice Wants to Promote Alicesonian Economics

Alice has a theory of how our economic system ought to work. She’s very excited about it and wants to set up a think tank to study and promote it. She forms a non-profit corporation and gets 501c3 status from the IRS. Once she does that (not hard), she donates some of her appreciated stock to her think tank and she’s off to the races.

Summary

Our stories about Alice and Bob illustrate three important aspects of our tax system:

Long-term capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income. This is why Bob the worker ends up with less than Alice the investor.

Capital gains taxes can be completely avoided when donating appreciated assets to a charity, even when one maintains a modicum of control over the money via private foundations or donor-advised funds.

Capital gains taxes are avoided by the step-up in basis when assets pass to heirs8.

Exploiting Capital Gains for Oligarch Wannabes

Now that we understand some of the basics of how capital gains are taxed, let’s dive a bit deeper and see what a huge win those preferential treatments are for the wealthy.

Deferred Taxation of Capital Gains

Let’s reconsider Alice’s investing success, this time assuming that our tax system didn’t advantage long-term capital gains. As before, Alice would start in 2017 by purchasing the 1,000 shares of Amazon for $795,990. But, this time, she’d have to pay income tax on the profit during the year. Unless she had cash sitting around uninvested, she’d have to sell some of her Amazon stock in order to pay the capital gains and net investment income taxes, which would reduce the number of shares of Amazon stock with which she started the next year. This would happen year after year:

Without the benefit of preferential treatment of capital gains, Alice would end 2021 with less than two-thirds of the Amazon shares she had with the preferential treatment.

Because this effect grows exponentially with time, the longer one holds the stock, the larger the bite if you had to pay taxes annually.

For example, in the 15 years since Amazon stock went public, it has increased in value by a factor of 1,906. Since I’m too lazy to do a chart like Alice’s above for all those years, let’s assume that the growth was constant over the 15 years. This would work out to a growth rate of 165.4% per year.

With no preferential treatment, every dollar invested when the stock went public would be worth $329. With preferential treatment, if she sold the stock after 15 years, every dollar invested would be worth $1,45210. That’s quite a difference.

Deferred taxation is immensely valuable with high-growth investments held over long time periods.

You might be thinking, though, that surely Alice is smart enough to pay her taxes by selling whatever investment she expects to earn the least in the future, not necessarily Amazon. True enough.

But if she were an oligarch wannabe experiencing this kind of explosive growth, there would be nothing else she could sell that could pay all the taxes.

Good thing this is moot, because in real life, capital gains taxes are deferred.

Deferred taxation of capital gains is a tremendous win for amassing wealth.

The Wealth-Building Triple Play: Buy — Borrow — Die

Oh, but it gets even better: Combine the deferred taxation of capital gains and the step-up in basis with the ability to borrow cheaply and you have an even bigger winner. Estate planners for the wealthy call this the buy-borrow-die strategy:

Buy (or be given) the stock

Kick the tax can down the road by borrowing, using your stock as collateral

Eventually, you’ll die. But don’t worry, with the step-up in basis, no capital gains taxes will ever be paid on the stock that you leave to you heirs

There are even low-interest loans for this purpose, as low as .87% for assets over $100M and only 3.2% for assets over $1M. Bank of America’s securities-backed loans dwarf its home equity loans.

And if our oligarch wannabe wants to be a philanthropist or build a great art collection, no problem, instead of waiting to die, simply create a non-profit private foundation, donate some of the stock to the foundation and, presto, no tax will be ever paid on all of the capital gains of the donated stock.

Even better, the full value of the donated stock can be deducted to offset taxes on profits on other investments (e.g., real estate).

Buy-borrow-die is the triple play of building and transferring wealth. Full deductibility of charitable donations with no capital gains is an extra bonus.

Maybe you’re not an oligarch wannabe; you still might want to check out some advice for “ordinary Americans.”

Diversionary Tactics

When one party or the other proposes changes to the tax code, most of the media coverage is about the maximum tax bracket for ordinary income (e.g., the Trump tax cuts lowered the “tax rate” from 39.6% to 37%). Yes, the income tax brackets affect what everyone pays, but those discussions are a diversion from the really important stuff, like do we continue to give preferential treatment to capital gains and do we retain the step-up in basis. That’s where the big money is for wannabe oligarchs.

When President Biden’s American Family Plan proposed eliminating the step-up in basis, it got little support even from most Democratic politicians. Few voters understand how the “buy-borrow-die” tax avoidance strategy works. But rest assured, the wealthy and near-wealthy understand this, as evidenced by the pushback the president’s plan received despite including measures to exempt $1 million in capital gains per person and measures to protect “family farms.”

Tax Expenditures

What Are They?

Tax breaks (i.e., exclusions, deductions, credits, and preferential treatment) in the federal tax system that cause the tax revenues to be lower than they would otherwise be according to normal tax law (sometimes called reference tax law) “in which all forms of income are taxed according to a single set of rates,” are called tax expenditures. The preferential treatment of capital gains and the step-up in basis are two examples of tax expenditures.

The name is apropos because tax breaks are no different than adding a typical expenditure to the budget, except that they don’t actually appear in the budget and they don’t have to be appropriated11. This is great for the politicians: There’s no need to pass the “Let Wealthy People Pass Untaxed Income to Their Heirs” act (aka, step-up in basis); just hide it mostly out of sight in the tax code.

We’ve seen how two particular tax breaks make it possible for individuals to accumulate vast wealth while avoiding taxation. In my experience talking to friends, relatives, and acquaintances, almost everyone understands marginal tax rates and maybe a few common deductions — that’s the media’s focus when they write about taxes — and almost nobody appreciates the importance to the wealthy of little-known tax breaks.

We also need to understand the answers to two other questions:

Tax breaks reduce tax revenue. Is the reduction significant on the scale of the federal budget?

Who benefits from tax breaks? The two breaks we’ve discussed so far are massively important for wealthy people. Do they also help poor or middle-class people? Are there tax breaks that help poor people too?

How Big Are They?

How significant are tax expenditures? The federal budget for 2019 was about $4.5T (yes, that’s trillion!), with revenues of $3.5T12, implying a $1T increase in the federal deficit. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which provides nonpartisan analysis for Congress that is generally well-respected, estimates that in 2019 tax expenditures totaled to about $1.6T. So, tax breaks are a big deal, larger than the annual increase in the federal deficit. Or, as the CBO puts it:

“That amount was equal to nearly half of all federal revenues, exceeded all discretionary outlays, and equaled 61 percent of all mandatory spending in the federal budget, which includes spending on Social Security and Medicare.”

Yet, tax expenditures generally fly under the radar in our country’s political debates.

Who Benefits from Tax Expenditures?

Do I really have to say this? The CBO analyzed 13 major tax expenditures, accounting for $1.2T of the $1.6T total and found that about half of the benefits from income tax expenditures (as opposed to payroll tax expenditures) benefit households in the highest quintile of the income distribution; households in the lowest quintile received 9% of the benefits.

Tax expenditures deliver more than 5 times as much benefit to the highest-earning fifth of households as to the lowest-earning fifth of households.

What Next?

We’ve seen some of the ways that our tax policy helps people become oligarchs and we’ve hinted at how oligarchs can use their wealth to influence our political discourse.

In the next issue, we’ll dive deeper into tax expenditures, looking at the other major tax expenditures and who they benefit. We’ll see that some tax expenditures benefit the poor and some benefit the middle and upper quintiles.

This will give us part of the context we’ll need in order to devise some win-win approaches to addressing some of the existential threats to American democracy.

I’ve made some simplifying assumptions: I’ve used 2021 tax rates for all years, assumed Alice had other money with which to support herself so she didn’t sell any of her Amazon stock and had no other income, assumed that both are single, that neither itemized deductions, that both are under 65, and I ignored state taxes.

Alice’s capital gains are taxed at multiple rates, as shown. She also pays the 3.8% net investment income tax on all investment earnings above a $200,000 threshold and the Alternative Minimum Tax, which is intended to close certain tax loopholes.

Although not illustrated by this example, most dividends — so-called qualified dividends — are also taxed at the lower capital gains tax rate, but must be paid annually. (This is the main reason that companies now prefer to return profits to shareholders via stock buybacks instead of dividends.)

This is a simplification. One’s charitable contribution deduction of non-cash assets is limited to 30% of one’s adjusted gross income. So, depending on Alice’s total income in 2021, she might only be able to claim 30% of her $3.4M contribution as a deduction in 2021. Not to worry. She can carry the rest of the contribution over to future years for up to five years.

Most brokerages (Fidelity, Schwab, Goldman Sachs, etc.) operate donor-advised funds for their clients.

The recommendations are followed as long as they meet IRS guidelines.

Disclosure: While very, very far from being billionaires, my wife and I use a donor-advised fund for tax reduction, for investing money we intend to use for future giving, and for the convenience that our brokerage’s donor-advised fund provides.

Note that a spouse can be an heir. Estate planners sometimes recommend that spouses own assets individually rather than jointly so that when the first spouse dies the surviving spouse can inherit the decedent’s assets and benefit from the step-up in basis to avoid capital gains taxes.

I’m assuming that the amount invested is large enough that essentially all of the gain is taxed at the maximum capital gains tax rate of 20%, plus the 3.8% net investment income tax.

The money grows to $1,906, then when selling the stock one has to pay 20% capital gains tax and 3.8% net investment income tax.

This is not quite true. Some tax expenditures that give money to the poor are listed in the budget. I leave it to you to consider why that might be.

Do you think eliminating capital gain tax and changing the rate to that of ordinary income would disincentivize ‘Alice’ from investing in the stock market? And if so, on a macroeconomic level would this harm the economy?

A fantastic description of the mechanics of our tax system .