Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

We saw last time that corporations are doing exceedingly well: Corporate before-tax profits are a larger share of GDP nowadays than they were throughout the entire period from the mid-1950s to the mid-2000s and, we the people, through our representatives, are being extraordinarily generous with low corporate tax rates and plentiful corporate tax breaks.

Today, we’re going to explore the main reasons that corporations are generating so much before-tax profit. (We discussed the tax side of the equation last time.)

Many large corporations are blaming their high prices on factors beyond their control: inflation, high wages, and supply chain problems. These are all plausible but they’re not the real cause of high prices, which is:

Corporations today have extraordinary pricing power, power over labor, and convenient excuses for high prices.

We’ll start our discussion by looking at the excuses.

Convenient Excuses

The Wage Excuse

Compensation Has Been Growing

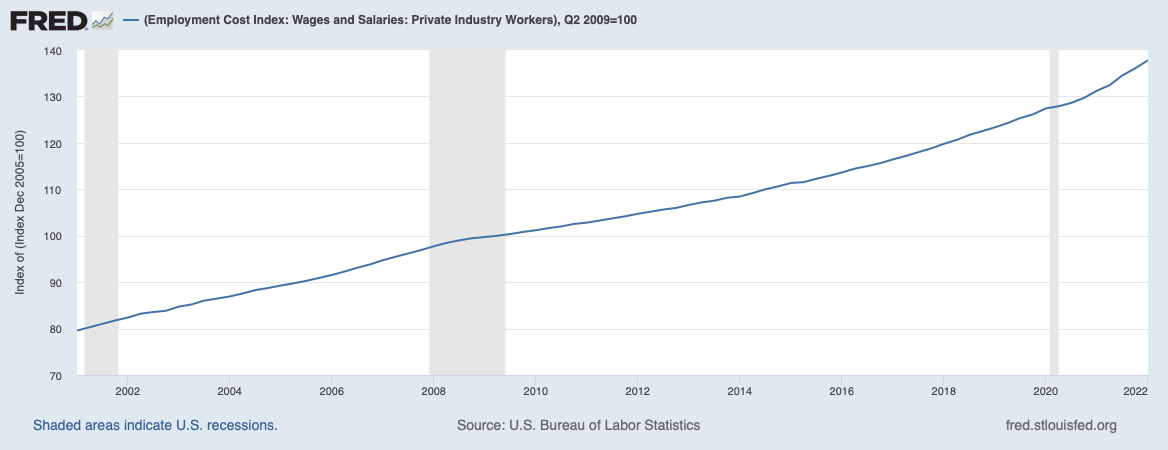

As corporations have been saying, wages have been rising. Benefits too. Here’s the employment cost index for private industry workers, which measures the total cost of compensating employees (wages plus benefits):

The index is shown here normalized to 100 at the end of the Great Recession. Employment costs have increased steadily, and are now almost 40% higher than in 2009.

Are Employees Getting a Great Deal?

Since the employment cost index measures the cost in dollars, it says nothing about what these compensation increases mean for employees’ standards of living. So, let’s look at the same graph normalized by the consumer price index, called real compensation, which shows us the changes in employees’ buying power:

Employees’ real compensation grew about 6.5% in the years between 2009 and 2020, but since 2020, has dropped around 3%.

Is Compensation Growth Forcing Prices Up?

Maybe corporations can’t afford to even keep their employees’ real compensation steady.

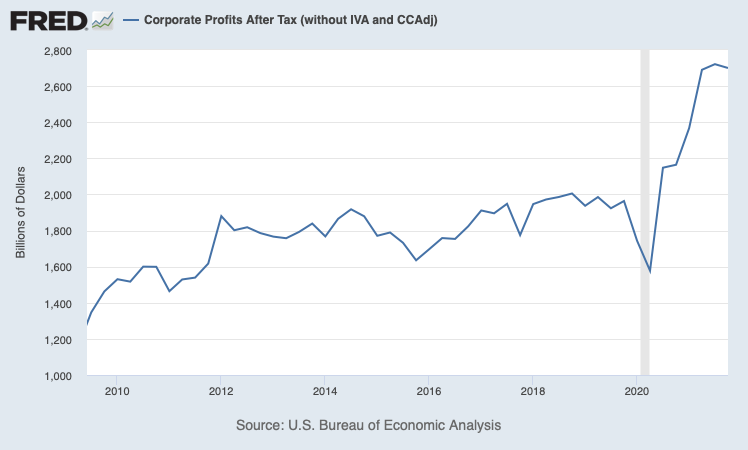

Here’s after-tax corporate profits in billions of dollars:

While employees’ real compensation decreased by 3% since 2020, after-tax corporate profit increased by about 69%.

The conclusion is clear:

Compensation growth is not forcing corporations to raise prices. The wage excuse is a lie.

The Inflation Excuse

Perhaps, inflated prices for the energy, raw materials, and services that corporations consume while producing consumer products and services are pressuring corporate profits.

This sort of inflation is not measured by the Consumer Price Index that we’re all used to. Instead, it is measured by the Producer Price Index (PPI), which measures inflation experienced by manufacturers and service providers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics conducts extensive surveys to measure the PPI.

Here’s what the PPI looks like since the end of the Great Recession, with the index normalized to 100 at that time.

The behavior of the PPI as we’ve come out of the pandemic-induced recession is striking, rising by about 41%. Companies providing consumer-level goods and services are experiencing inflation in what they consume.

Nevertheless, in that same period since January 2020, corporate profits are up about 69%.

Yes, inflation affects corporations, but coming out of the pandemic-induced recession,

Corporations have raised their prices and hence their profits even faster than inflation has raised the cost of their inputs.

The Supply Chain Excuse

Supply chain problems raise prices for manufacturers and can limit their ability to produce their products. If a corporation can’t meet the demand for their product, their profit is going to drop unless they can raise prices enough to compensate for the lower volume.

You guessed it — that’s exactly what’s happening in some important industries. Take automotive. Here’s one view:

“The pandemic — or, more accurately, the pandemic-fueled microchip shortage — has been an absolute bounty for automakers, altering the supply-demand equation that has long plagued the auto industry.”

Companies report this in their own investor materials. Here’s a slide from Ford’s 2021 earnings presentation (green highlighting mine):

Here’s how to interpret the finance-speak:

“EBIT margin of 8.4%”: profit margin before interest and taxes of 8.4%, noting that this is the best since 2017

“strong pricing”: We were able to raise our prices

“mix”: we directed our limited supplies to our most profitable products

“more than offset …”: we paid more for materials, we sold fewer vehicles, we made more money

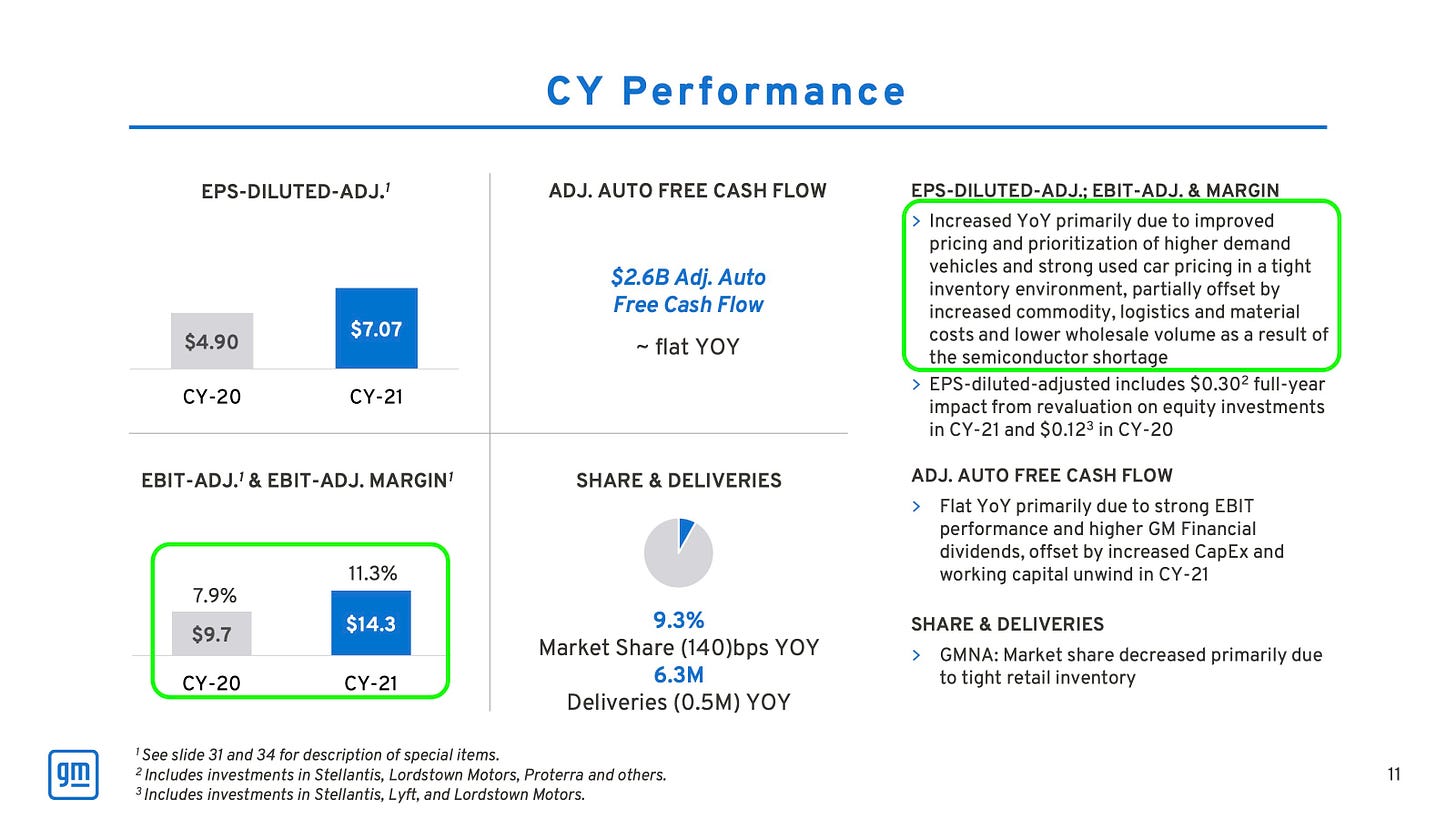

Similarly, GM showed this slide (again, green highlighting mine):

The interpretation is similar, with profit margin increasing from 7.9% in 2020 to 11.3% in 2021.

I could go on and on with more automotive companies and with companies in other industries, but you get the picture.

Capitalism at Work

We’ve seen that corporate profits are way up, even though wages, inflation, and supply-chain issues have increased corporations’ costs. This can only happen because they’ve increased their prices faster than their costs have risen.

Corporations are soaking consumers and driving up inflation while deflecting blame elsewhere.

Should we be surprised? No. Corporations are operating in a system that we’ve allowed them to create over the last 40 years.

The Shareholder Value Mantra

This is how our system works. Corporations make profits for their investors. Corporations also provide products and services that consumers need or want, products consumed by other corporations, and jobs for many people. They impact our environment — for good and ill, they participate in the communities in which they operate — for good and ill, and they influence our political system — for good and ill.

Since the early 1980s, Milton Friedman’s doctrine that the social responsibility of a corporation is to increate its profits has taken hold, leading to the mantra of shareholder value, espoused in business schools and by Jack Welch (CEO of GE) and other corporate executives:

The purpose of a corporation is to maximize shareholder value.

Ignoring Other Stakeholders

Over the last 40 years, corporate boards have coupled CEO and other senior executive compensation to the price of the company’s stock, creating a maniacal focus on maximizing shareholder value.

This focus has changed the nature of the relationship between corporations and other stakeholders, including customers, employees, and communities:

Employees are often managed as “resources,” with work being moved to lowest cost locations around the world, and compensation (both wages and benefits) reduced as much as possible.

Corporations move in and out of communities with little thought of the impact on those communities, often negotiating tax breaks as an enticement to create jobs when they enter a community and leaving economic devastation when they leave.

Corporations build political power through extensive lobbying, campaign contributions, and support of PACs. They wield this power to further maximize shareholder value through tax breaks and favorable laws and regulations, usually at the expense of communities, the environment, and employees.

The story, however, is not all bleak. Modern corporations have helped to create an economic and innovation engine that is unparalleled in history. Some people have previously unimaginable wealth and opportunities. The economic standard of living for many Americans is better than ever.

Yet many in American and elsewhere struggle to obtain decent food, housing, education, and healthcare.

Unfettered pursuit of shareholder value to the exclusion of all else leads to costs borne by others in society, while corporate owners profit. There must be counter forces that create a suitable balance between corporate profit — which is essential to continued economic growth and innovation — and the needs of other parts of society.

Our next step is to understand some of the factors that tilt the balance in one direction or the other.

Declining Worker Power

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in 2013 our economy produced nine times more goods and services than in 1947, with little increase in hours worked. In other words, labor productivity, defined as the amount of GDP produced by an hour of labor, increased nine-fold in that period.

Rising productivity increases standard of living because the economy produces more goods and services for a given amount of labor. Traditionally, the benefits of rising productivity have been shared through increased compensation.

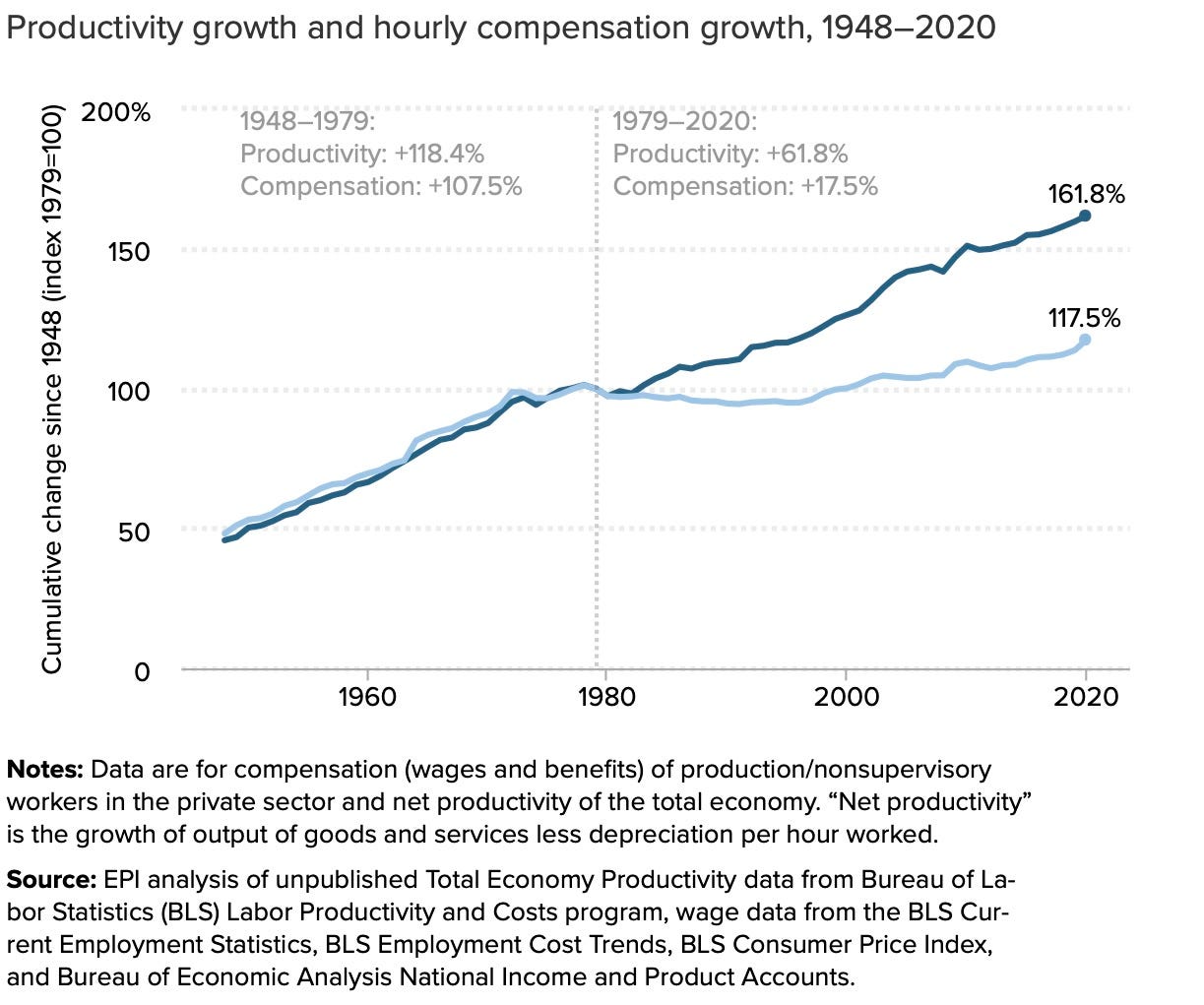

Starting in the early 1980’s, however, the nature of this sharing changed dramatically as shown by this analysis from the Economic Policy Institute:

Corporations used to share the benefits of productivity increases with their employees. That changed dramatically as the shareholder value mantra took hold and corporations worked the political system to ensure that the federal minimum wage stagnated, labor law changes and low enforcement aided companies in suppressing unions and the threat of unionization, and high unemployment was tolerated in the name of managing inflation.

Some prominent economists believe that declining worker power entirely explains the rapid growth in corporate profits, and the distribution of those profits primarily to capital and not labor. Others believe that declining competition is also a significant cause of the rapid growth in corporate profits.

Declining Competition

Corporate consolidation has been gaining speed and scope for several decades for a variety of reasons, including lax anti-trust enforcement, technological changes, and the rise of “winner take all” markets.

Here are a few examples:

Many well-known retail brands are controlled by a few large companies that control seemingly competing brands.

Corporate consolidation in agriculture, with four companies controlling the corn and soybean seed markets, and four large meatpackers controlling 66 percent of the hog market.

Four airlines dominate domestic air travel

Many Americans are served by only one broadband internet provider, while others have no access to broadband

Healthcare in many locations is provided by only a few major providers, who have been buying up most independent medical practices.

With consolidation into a few dominant companies in many markets, those companies can (and do) raise prices, lower quality to decrease costs, prevent new competitors from entering the market, decrease worker compensation, and treat workers poorly, all in the name of maximizing shareholder value.

Consolidation can create both monopoly, in which there is a single or small number of sellers in a market for particular goods or services, and monopsony, in which there is a single or small number of buyers in a market.

Monopoly power allows sellers to raise prices and profits. If there are significant barriers to entry for new competitors, prices and profits can be very high because buyers have no alternative. Broadband internet is a good example of an industry with a lot of monopoly power and significant barriers to entry, which is one reason that Americans pay much higher prices for broadband internet than in many other countries.

Monopsony power allows buyers to force prices down for the products they buy because sellers have no alternatives. The meat packing industry is an example of monopsony power, in which farmers must sell to one of a few meat packers , who can drive down the prices they pay since the farmers have no alternative. Large, dominant retailers like Walmart and Amazon also have monopsony power and use it to drive down the prices they pay for merchandise. Book publishers, for example, have little choice but to yield to Amazon’s pricing demands.

Monopsony power can also help depress wages. If there are only a few major corporations in a particular industry, they won’t compete for labor because people working in that industry will have little choice.

Some companies have both monopoly and monopsony power. The meat packers are a good example because they control both the buying and selling of meat.

Summary

We’ve seen that corporate profits have been soaring due to several factors:

Declining competition in many industries because of both monopoly and monopsony power.

Not sharing the benefits of rising labor productivity with labor.

As we’ve been coming out of the pandemic-induced recession, corporations have been raising prices rapidly, using rising wages, rising inflation, and supply chain problems as convenient but false justifications for their price increases.

Much of this behavior has been enabled by 40 years of corporate obeisance to the mantra of shareholder value, reshaping our economic landscape by exerting increasing political power to change laws, regulations, and enforcement policies to support increased shareholder value.

What Next?

Corporate wealth and power is being wielded in ways that threaten our democracy. We’ve now seen — in this and the previous issue — how our system has changed to help large corporations earn higher profits and keep more of it.

Our next issue’s topic is how campaign finance laws have been changed to allow companies and very wealthy individuals essentially unlimited power in our political system.

With the campaign finance situation under our belts, we’ll have the background we need to discuss, in the following issues, proposals for win-win solutions to some of our country’s problems.

Excellent concise overview of a complex topic. Since corporations exist (1) to maximize shareholder value - by maximizing profits on (2) delivered offerings to customers, and (3) provide jobs for employees - it seems increasingly logical to do a better job of ensuring when a customer buys the product, they also get a fractional share of stock in the company (deposited in an individual retirement account). A fractional share of an index fund might be even better, as a way to ensure the people are more equitably benefiting from the success of corporations as innovation engines that raise quality of life for citizens. Why not "buy2invest" systems change to better align incentives of corporations, people, and governments (which have a special responsibility to their elder citizens in the form of social security)?