Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

Corporate wealth and power is one of the four existential threats to our democracy that we discussed in the newsletter issue titled Taking Stock. We are working our way through these threats so that we have a shared understanding from which to work on win-win proposals for helping to preserve our democracy.

This newsletter issue starts our look at corporations. How are they faring in today’s economy? In the media you’ll see and hear some folks griping about rising wages, excessive regulation, and taxes constraining corporate profits and other folks griping about corporate profits being too high. What’s the reality?

How Are Corporations Doing?

Corporations are doing great. Let’s look at their profits, after taxes, relative to the size of the economy.

The size of the economy is typically measured by our gross domestic product (GDP). As the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) puts it, GDP is “[a] comprehensive measure of U.S. economic activity. GDP measures the value of the final goods and services produced in the United States (without double counting the intermediate goods and services used up to produce them). Changes in GDP are the most popular indicator of the nation's overall economic health.” (The BEA has a simple two-page explanation of GDP, which you may find helpful.)

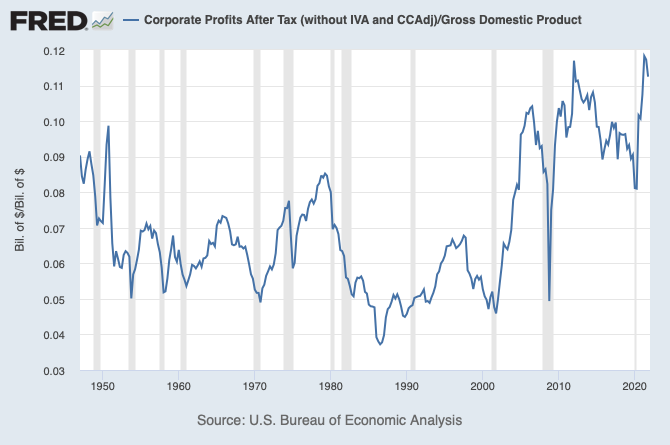

We can understand how corporations are doing by looking at their profits after paying taxes, normalized as a fraction of GDP. Here is the historical data from the BEA:

After-tax corporate profits as a fraction of GDP reached an all-time high in 2021.

So, despite the griping about wage growth, taxes, and regulation, corporations have never taken such a high share of GDP.

Profits or Taxes?

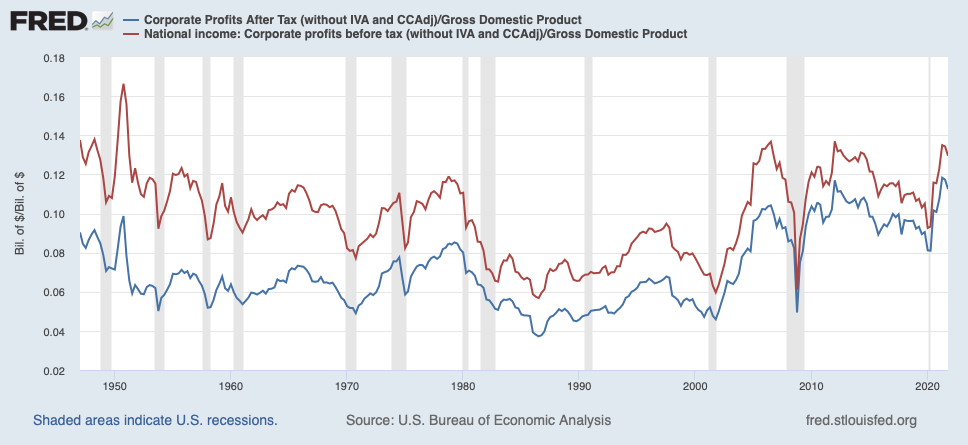

To understand why this is so, we need to look both at corporate profits before taxes and at how much of a bite taxes are taking from those profits. Here’s the same graph (the scales are different), this time also showing before-tax corporate profits (red):

Corporate before-tax profits are a larger share of GDP nowadays than they were throughout the entire period from the mid-1950s to the mid-2000s, just before the bubble burst creating the depression of the late 2000s.

After-tax profits (blue) are lower than before-tax profits,1 with the gap between the two lines showing the effect of taxes paid. The trend of the two lines getting closer together indicates that taxes paid are declining. (We’ll see this more clearly below).

Corporations are doing well both because their before-tax profits are increasing and because their taxes are decreasing.

Corporate Income Taxes

Let’s start with understanding the tax aspect of why corporations are so profitable right now.

What Are the Rates?

The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) set the federal tax rate on corporations to a flat rate of 21% (flat meaning that there are no brackets — this is the rate on all corporate profits), down from a top marginal tax rate of 35% between 1993 and 2017 and substantially higher rates in the 1950’s through 1986. Indeed, the top marginal corporate income tax rate hasn’t been this low since before World War II:

The advertised corporate income tax rate of 21% is historically low.

What Do Corporations Actually Pay?

We know from our study of individual taxes that the stated marginal tax rate is not all that matters.

Let’s do a back-of-the-envelope analysis to see what’s going on. According to the BEA, at the end of federal fiscal year 2021 corporate pre-tax profits were $3.1 trillion. Corporate federal income tax receipts for fiscal year 2021 were $370 billion, as reported by the Congressional Budget Office. So, on average, corporations paid 11.9% in federal income tax, about 43% lower than the advertised rate.

As you might expect with all things tax, appearances are deceiving. The advertised rate of 21% is not what corporations actually pay.

A more detailed analysis, by the non-partisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), of corporate tax avoidance2 in the first year of the TCJA examined the financial filings of Fortune 500 companies. ITEP identified 379 of those companies that were both profitable and reported enough information to be able to estimate their effective tax rate. Among those 379 Fortune 500 companies, they found an even lower average effective rate of 11.3%, a bit more than half of the advertised rate.

Moreover, 91 of the 379 corporations paid no federal income taxes on their 2018 US income, including Amazon, Chevron, Halliburton, and IBM; another 56 companies paid effective rates between 0 and 5 percent.

If you wish to congratulate the CFO’s of the companies that pay the lowest effective rates, you can look at ITEP’s spreadsheet listing the 379 companies and what they each paid:

Many Fortune 500 corporations pay little or no corporate income taxes.

Corporations are Getting a Great Deal

Last time we talked a lot about tax expenditures. (If you haven’t read that, think “tax break” when I say “tax expenditure.”) The CBO’s analysis of 2019 data shows that total tax expenditures amount to 7.8% of GDP. Of that, the largest portion affects individuals through individual income tax expenditures (5.8% of GDP) and payroll tax expenditures (1.0% of GDP), and those are what we focused on last time’s discussion of redistribution of wealth.

That leaves another .9% of GDP in corporate tax expenditures, which, with 2019 GDP about $21.4T, amounts to $193B. The CBO reports 2019 corporate income tax receipts of $230B, so corporate income tax expenditures were about 84% of receipts.

Corporations are currently getting a great tax deal: a historically low 21% tax rate, plus the benefit of tax expenditures that are almost as large as the taxes they actually pay.

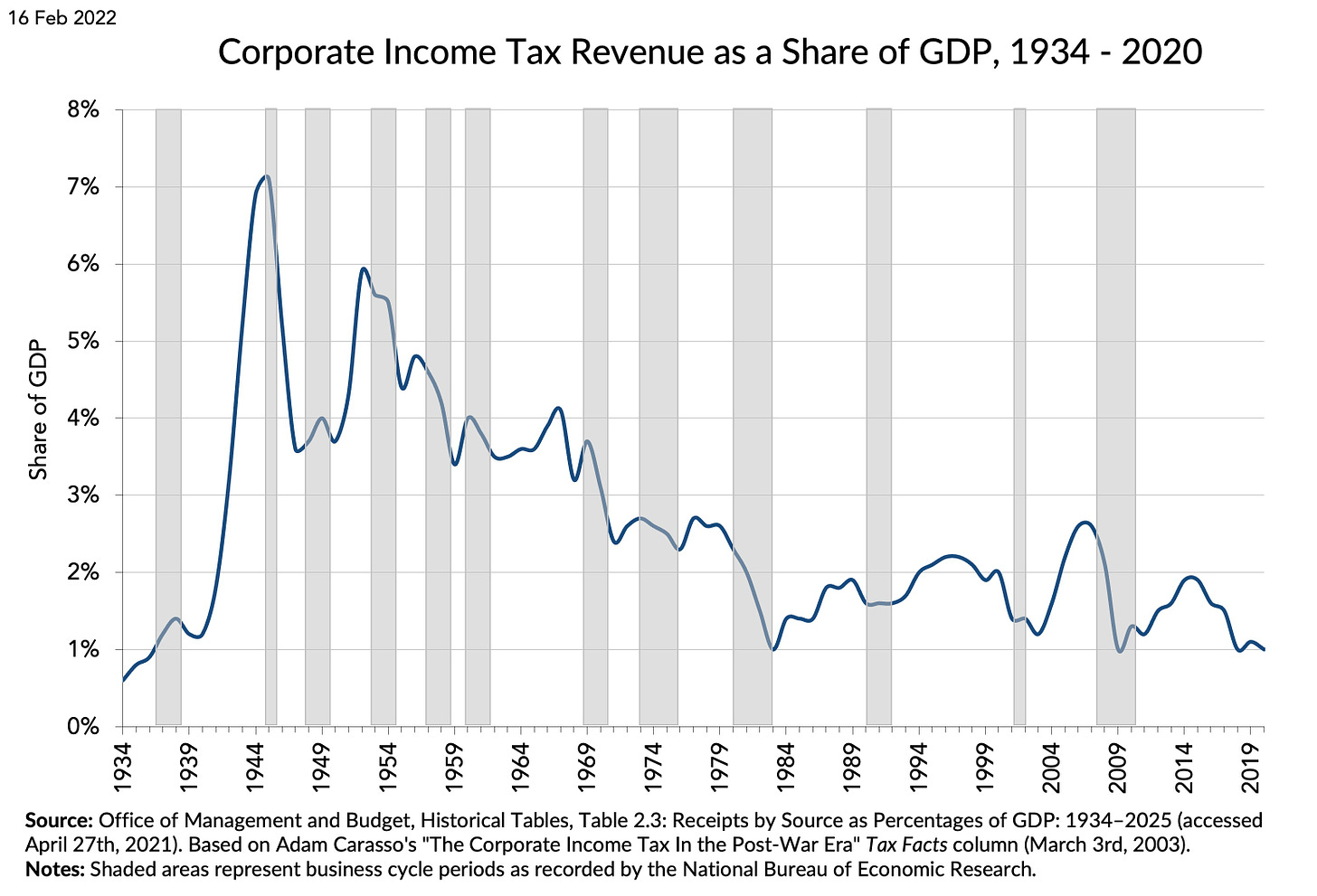

In fact, as measured by corporate income tax as a share of GDP, corporations haven’t had a better deal since 1937:

Corporate income taxes collected are at historically low levels, having declined from 7% of GDP during World War II, down to 1% of GDP in the Reagan administration, hovering around 2% of GDP during the 90’s, and returning to around 1% as a result of the TCJA.

Corporate Tax Expenditures

For last issue’s discussion of individual tax expenditures I relied on a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis. Unfortunately, I have been unable to find an analogous CBO analysis of corporate tax expenditures.

Instead I’ve used estimates of corporate tax expenditures from both the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) and the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). A 2019 report from the Tax Policy Center lists and explains the largest ten corporate tax expenditures based on numbers from the OTA and JCT (which differ). We’ll discuss the top three.

#1: Reduced taxes on income from foreign subsidiaries

Many US corporations control foreign subsidiaries. The official term is controlled foreign corporations (CFCs). Special rules govern how earnings from CFCs are taxed. The rules are easy for corporations to game.

Ordinarily, US corporations are taxed on their worldwide income, with a credit for foreign taxes they pay. But tax on non-US income is only collected when the money is brought into the US. So, many corporations hold the profits from their CFCs in other countries to avoid taxation.

Indeed, many companies intentionally shift profits from the US to other countries to avoid US taxes. This is easy to do with intangible assets like patents and software, which are easy to “move”:

Transfer your software and patents to a CFC located in a low-tax country

The CFC charges the US company high prices to use that intellectual property, which lowers US profits, which is where the taxes are high

Pay (low) foreign taxes on the CFC’s profit from licensing the intellectual property to the US company

Avoid paying US taxes on the CFC’s profit by leaving the profits in the foreign country

Apple, for example, has used this strategy.

The TCJA changes the game in some important ways.

First, no US tax is levied on profits of CFCs that are less than 10% of the value of a company’s foreign tangible assets (equipment, structures). The idea is that 10% is a reasonable return on investment in tangible assets, so the tax system assumes that that return is from doing real business in the foreign country. It will be taxed by the foreign country.

Second, profits above this 10% threshold are consider “excess profit” in the sense that they’re assumed to be the result of shifting easy-to-move intangible assets (e.g., intellectual property) to CFCs rather than profit from actually doing business in the CFC. The fancy name is “Global Intangible Low-Tax Income”(GILTI). Congress has some great acronym creators.

GILTI income is taxed by the US at half the normal corporate rate, i.e., half of 21%, or 10.5%, and special rules reduce the credit for foreign taxes on GILTI income. The reduced rate is intended to help provide a level playing field between US and foreign-resident multi-national corporations.

All of this is immensely complicated and the rules are evolving and new games are developing. The good news is that this has opened up new business opportunities for GILTI consulting services.

The JCT estimates a tax expenditure of $309B over 2019-20223, making it the largest corporate tax expenditure.

#2: Accelerated depreciation of assets

Ordinarily, when a business buys equipment it can deduct the cost of the equipment from its earnings over the expected lifetime of the equipment. For example, when a business buys a machine for $10,000 with an expected lifetime of 5 years, it could deduct $2,000 each year using something called straight-line depreciation.

Of course, there are multiple ways to calculate depreciation and many rules and special cases: To cure insomnia, read the IRS’s 112-page Publication 946 entitled “How to Depreciate Property”, plus separate publications on depreciating cars, residential rental property, home office space, and farm property. Or you might be interested in the new rules introduced in 2021 on depreciating certain race horses.

Let the games begin.

On top of this already complex system, the TCJA introduced so-called Section 168 “bonus” depreciation, which allows qualifying assets purchased between 2018 and 2022 to be fully expensed, that is, to be deducted 100% immediately, instead of over time4. Again, the rules are complex and there are many opportunities for gaming.

The JCT estimates the tax expenditure for accelerated depreciation is $253B over 2019-2022, making it the second largest corporate tax expenditure.

#3: 20% deduction for Qualified Business Income

The TCJA allows individuals to deduct 20% of qualified business income (QBI) from domestic passthrough businesses. What does this mean?

First, what is a domestic passthrough business? The domestic part is pretty clear. A passthrough business is one where the business doesn’t file its own corporate tax return, but instead the income “passes through” to the business’s owners, who pay individual income tax on that income. Companies like partnerships, LLCs, sole proprietorships, and S corporations are passthrough businesses. Over 90% of businesses are passthrough businesses.

Second, what is qualified business income? The qualifications are complex and arbitrary, making the rules difficult to understand and interpret.

Here’s what the IRS has to say about it: “The QBI Component is subject to limitations, depending on the taxpayer’s taxable income, that may include the type of trade or business5, the amount of W-2 wages paid by the qualified trade or business and the unadjusted basis immediately after acquisition (UBIA) of qualified property held by the trade or business. It may also be reduced by the patron reduction if the taxpayer is a patron of an agricultural or horticultural cooperative.” Pretty clear, huh?

So, let’s say you are an owner of a small company that provides engineering services. The company’s earnings pass through to you. Assuming your business qualifies, you get to deduct 20% of the passthrough earnings on your income taxes, effectively lowering the tax rate on those earnings.

Let the games begin.

Since business income passed through to you is now more attractive than wages, reduce the wages you pay yourself from the business. Now you can get more passthrough income, giving you a larger QBI deduction.

Or, suppose you are a physician in a medical group. Health is not a qualified business (why not? — who knows). But suppose you combine your medical group with a firm supplying equipment. Now, maybe the business is a qualified business. So, reduce your wages, increasing the business’s earnings, and pass the earnings through to get the 20% QBI deduction.

The JCT estimates this tax expenditure at $226B for 2019-2022.

The Hit from Tax Expenditures

Just the top three corporate tax expenditures we’ve discussed cost $778B over 2019-2022, an average of $194B a year. The JCT estimates for the remaining top-ten corporate tax expenditures amount to $291.2B over the same 4 years, for an average of $72.8B a year.

That’s a total of $267B a year from the top ten corporate tax expenditures.

Summary

Corporations are doing exceedingly well right now. Here are the key points to remember:

Corporate before-tax profits are a larger share of GDP nowadays than they were throughout the entire period from the mid-1950s to the mid-2000s

After-tax corporate profits as a fraction of GDP reached an all-time high in 2021.

Corporations are currently getting a great tax deal: a historically low 21% stated tax rate, plus the benefit of tax expenditures that are almost as large as the taxes they actually pay, reducing the average effective tax rate to around 11.9%.

Corporate income taxes collected are at historically low levels, around 1% of GDP.

Corporate taxation is enormously complex, creating many opportunities for gaming the system.

What’s Next?

Corporate wealth and power is one of the existential threats to our democracy. We’ve seen that corporations are both generating record amounts of profit and our tax system is letting them keep more of it than ever.

Next time we’ll look at the conditions that are allowing corporations to be so profitable in the first place.

We’ll then turn our attention to how campaign finance laws have been defanged, helping us to understand how wealth turns into power.

If you continue on this journey, we’ll then start discussing ideas for win-win solutions to help preserve our democracy.

It is a long journey — I hope you’ll stick with me on it.

While this is true in aggregate, some corporations get large enough tax benefits that their after-tax profits are higher than their before-tax profits.

Corporate tax avoidance is taking steps that are legal to lower taxes, as opposed to tax evasion, which is takings steps to lower taxes that are illegal. We’re going to pretend we live in fairyland, where all corporations obey the law.

The OTA estimates a $159B tax expenditure, probably because the OTA includes in their estimate a one-time offsetting tax on repatriating profits held by CFCs.

After 2022, the accelerated depreciation is phased out at 20% per year.

Thanks - again learned a lot. My three questions: (1) how do public and private corporation compare in terms of taxes paid? (2) are corporate tax returns available to the public? (3) how can the complexity of the global economic system be modeled as a simulation/education tool?