Turning Money Into Power

Campaign finance: turning money into power without accountability

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

We’ve discussed how our tax system, together with the way we treat labor and allow corporate consolidation, helps create unimaginably wealthy individuals and corporations.

Although there are many reasons to care about this, our current focus is threats to our democracy, so we’re going to explore how our campaign financing system has been shaped to give wealthy individuals and corporations immense political power.

Does Money Really Buy Power?

Donald Trump and Joe Biden agree that money buys power:

“I gave to many people, before this, before two months ago, I was a businessman. I give to everybody. When they call, I give. And do you know what? When I need something from them two years later, three years later, I call them, they are there for me. And that’s a broken system.” — Donald Trump, during the August 6, 2015 Republican candidates debate

“You have to go where the money is. Now where the money is, there’s almost always implicitly some string attached. ... It’s awful hard to take a whole lot of money from a group you know has a particular position then you conclude they’re wrong [and] vote no.” — Vice President Joe Biden, speaking in 2015 at the Make Progress National Summit

It is worth the 8 minutes to watch Biden’s complete remarks (the quote above is at timestamp 2:58):

Trump and Biden are hardly unique: Other politicians have made similar remarks.

Houston, we have a problem. A huge problem:

Political spending in the 2020 election was $14.4B, more than twice the spending for the 2016 election

Organizations of various kinds spent $3.7B in 2021 on lobbying

How much influence do you think your letter or call to your Congressperson or Senator has compared to this kind of spending?

If you’re more swayed by science than by intuition, political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page have done analyses that show that ordinary citizens have far less influence on public policy than affluent citizens and organized interests. An easier read with similar conclusions appears here.

Basics of Campaign Finance Law

Our campaign finance law is a mish-mash of federal laws, 50 sets of state laws, and court rulings. We’re going to discuss federal law, which governs campaigns for all federal offices. The complexity of just federal law is mind boggling.

Moreover, enforcement of the federal laws is intentionally weak: The Federal Elections Commission (FEC) is set up to fail because it is “led by six commissioners, no more than three of whom can belong to the same party” and all decisions require four votes. In real life, this means that there are usually three Republican and three Democratic commissioners1, who deadlock. It is so bad that the FEC often doesn’t defend itself in court, a strategy that Democratic commissioners use in the hope that the courts will enforce regulations, most of which Republican commissioners refuse to allow the FEC to enforce.

Federal campaign finance law is complex and riddled with loopholes. The federal agency charged with enforcing the law is structured to fail.

Contribution Limits

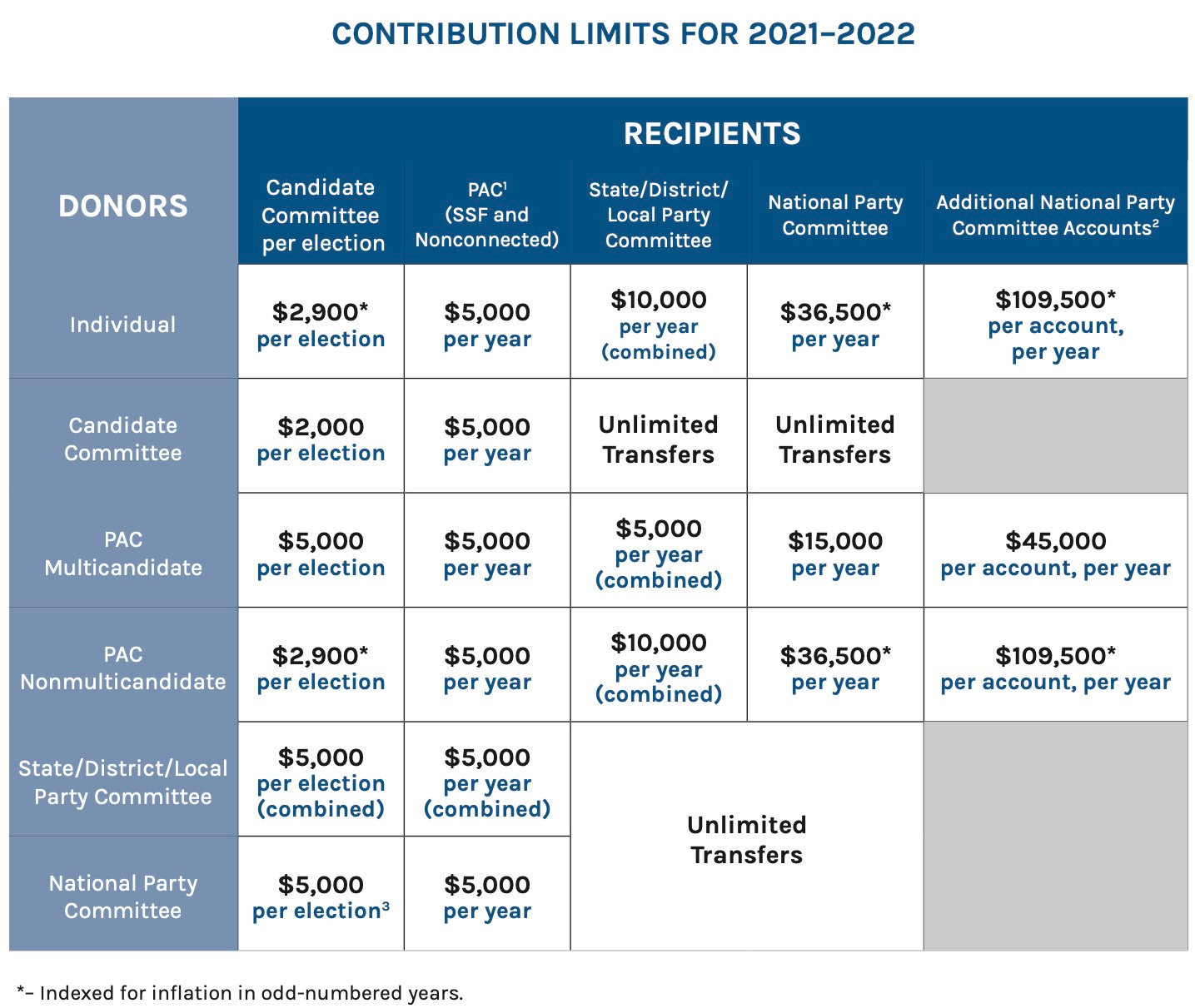

Contributions to various kinds of political organizations are limited, as shown in the table:

The word committee has a specific meaning: A candidate committee is an organization authorized by a candidate that receives and spends money for the purpose of electing the candidate. A party committee is an organization authorized by a political party to receive and spend money for the purpose of supporting the aims of the party, including electing candidates.

If you’re like me, you’ll probably understand the upper-left cell. The “per election” phrase means that you can give up to $2,900 to Suzy Politician’s candidate committee for her primary election campaign, another $2,900 if there’s a runoff election, and another $2,900 for her general election campaign. You can do this for as many recipients as you wish — there are no limits on how much money you can spend on political contributions2.

Beyond this, it is probably murky. I’ll guide you through it, but I have to warn you that I’m not an expert, I’ll be skipping a lot of often ambiguous detail, and it can still get dull. If it gets too dull, just skip to the next section.

Contributions to National Committees

The two (major) parties each have three national party committees:

National committee: Democratic National Committee (DNC); Republican National Committee (RNC)

House campaign committee: Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC); National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC)

Senate campaign committee: Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC); National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC).

Each of these committees has separate, quite large, contribution limits.

National committees can receive large contributions from individuals and PACs, and unlimited contributions from candidate committees.

The rightmost column in the money chart applies to so-called additional national party committee accounts, national party committees’ accounts for the presidential nominating convention, recounts and other legal proceedings, and national party headquarters buildings.

Additional national party committee accounts can receive large contributions from individuals and PACs (see below).

To give you a sense for the staggering amount of money these committees wield, here are the amounts for 2020 (data from Ballotpedia):

National committees: $649M (R) and $399M (D)

Senatorial committees: $271M (R) and $241M (D)

Congressional committees: $196M (R) and $221M (D)

Support or lack of support from the national committees can make or break a Congressional or Senatorial candidate’s campaign, giving the national committees tremendous power over candidate choice, even in primaries.

Contributions to State, District, and Local Party Committees

State, district, and local parties also can have similar committees. The details depend on state laws but are often analogous to the national structures. Regardless, there are similar but smaller limits on contributions to these committees.

Federal law allows unlimited transfers among national, state, district, local and committees.

Contributions to Candidate Committees

A candidate authorizes his or her candidate committee to receive money and make expenditures on his or her behalf. Where does the money come from?

From Individuals and Other Candidates

Individuals, other than foreign nationals, can contribute to the candidate committee up to the $2,900 limit per election. Donors can contribute to as many candidates as they’d like.

Other candidate committees can contribute up to $2,000. Candidates with extra money can help other like-minded candidates, garnering favor at the same time.

From the Candidate

Candidates can contribute or loan their own funds to their committee for campaign purposes without limit.

It helps to be a wealthy candidate.

Loans are interesting: Suppose I said to Suzy Politician, “I’ll give you $500K to repay some of the money you loaned to your campaign.” The money would go not into her campaign committee, but directly into her pocket. Kinda like a bribe. Don’t you think that she’d be likely to help me when I ask while she’s in office?

To limit this kind of bribery, the 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign financing act limited loan repayments obtained from donors after the election to $250K. Well, that was then.

Turns out that Senator Ted Cruz loaned $260K to his 2018 campaign. He sued to get back the $10K, hoping to overturn the limit. On May 16th, 2022, SCOTUS3 threw out the limit.

Here’s how Justice Kagan4 put it in her dissent (p. 28):

“A candidate for public office extends a $500,000 loan to his campaign organization, hoping to recoup the amount from benefactors’ post-election contributions. Once elected, he devotes himself assiduously to recovering the money; his personal bank account, after all, now has a gaping half-million-dollar hole. The politician solicits donations from wealthy individuals and corporate lobbyists, making clear that the money they give will go straight from the campaign to him, as repayment for his loan. He is deeply grateful to those who help, as they know he will be—more grateful than for ordinary campaign contributions (which do not increase his personal wealth). And as they paid him, so he will pay them. In the coming months and years, they receive government benefits—maybe favorable legislation, maybe prized appointments, maybe lucrative contracts. The politician is happy; the donors are happy. The only loser is the public.”

Bribe away!

From Corporations, Labor Unions, and National Banks

Nope — not allowed. Warning: Huge loopholes ahead!

From Corporate and Labor Political Action Committees (PACs)

A corporation or labor union can create and support financially a political committee, paying administrative and solicitation costs, but not otherwise contributing to it. These are commonly called Corporate (Labor) Political Action Committees (PACs). The FEC jargon is separate segregated fund (SSF); that’s what you’ll see in the contribution limits table.

Many large corporations create corporate PACs and encourage (sometimes to the edge of coercion) their senior employees and their families to contribute. They brand their PACs as “employee political action committees” but employees have no input to how the money raised is spent. Indeed many corporate PACs work against their employees’ interests.

Similarly, labor unions also create labor PACs and solicit contributions from union members.

Contribution limits for corporate and labor PACs depends on how many candidates the PAC supports and how many people contribute to the PAC.

From Party Committees

Each party committee can contribute $5,000 to any candidate committee. Additionally, a national party committee and its Senatorial campaign committee can contribute up to $51,200 (combined) to each Senate candidate.

Although there are low limits on how much national party committees can give to candidate committees, they are free to spend whatever they want to support candidates.

It is common for these committees to make large advertising buys and to fund direct mailings to voters. This is one reason the national party committees have so much power over the choice of candidates in Congressional and Senatorial elections.

Leadership PACs

In addition to their campaign committees, politicians leaders often establish independent committees to support other candidates for various offices. Called leadership PACs, they are controlled by a candidate or an individual holding a federal office (Senator, Congressperson), but are not affiliated with the controlling person’s candidate committee. Leadership PACs are subject to contributions limits.

According to a report by Issue One and the Campaign Legal Center, 92% of members of Congress have leadership PACs.

Political Spending

Leadership PACs allow one politician to help other like-minded politicians. More cynically, politicians adept at fundraising can control other politicians with the not-so-subtle suggestion that there are strings attached to this money. It is also an effective way for people seeking leadership positions to curry favor with those whose votes they’ll need.

For example, according to OpenSecrets.org, Mitch McConnell’s leadership PAC, the Bluegrass Committee PAC, raised $2.1M in 2020 and spent $1.6M, making contributions to Republican House and Senate candidates, other PACs, and various national and state Republican Party entities. Similarly, also according to OpenSecrets.org, Charles Schumer’s leadership PAC, Impact (Schumer), raised $1.8M and disbursed $1.6M in a similar manner to Democratic candidates, PACs, and party entities.

In the flush world of national politics, a few million here, a few million there doesn’t seem like much. But, according to another report by Issue One, the 500 leadership PACs controlled by sitting members of Congress raised more than $150M between January 1, 2017 and September 30, 2018. This is real money.

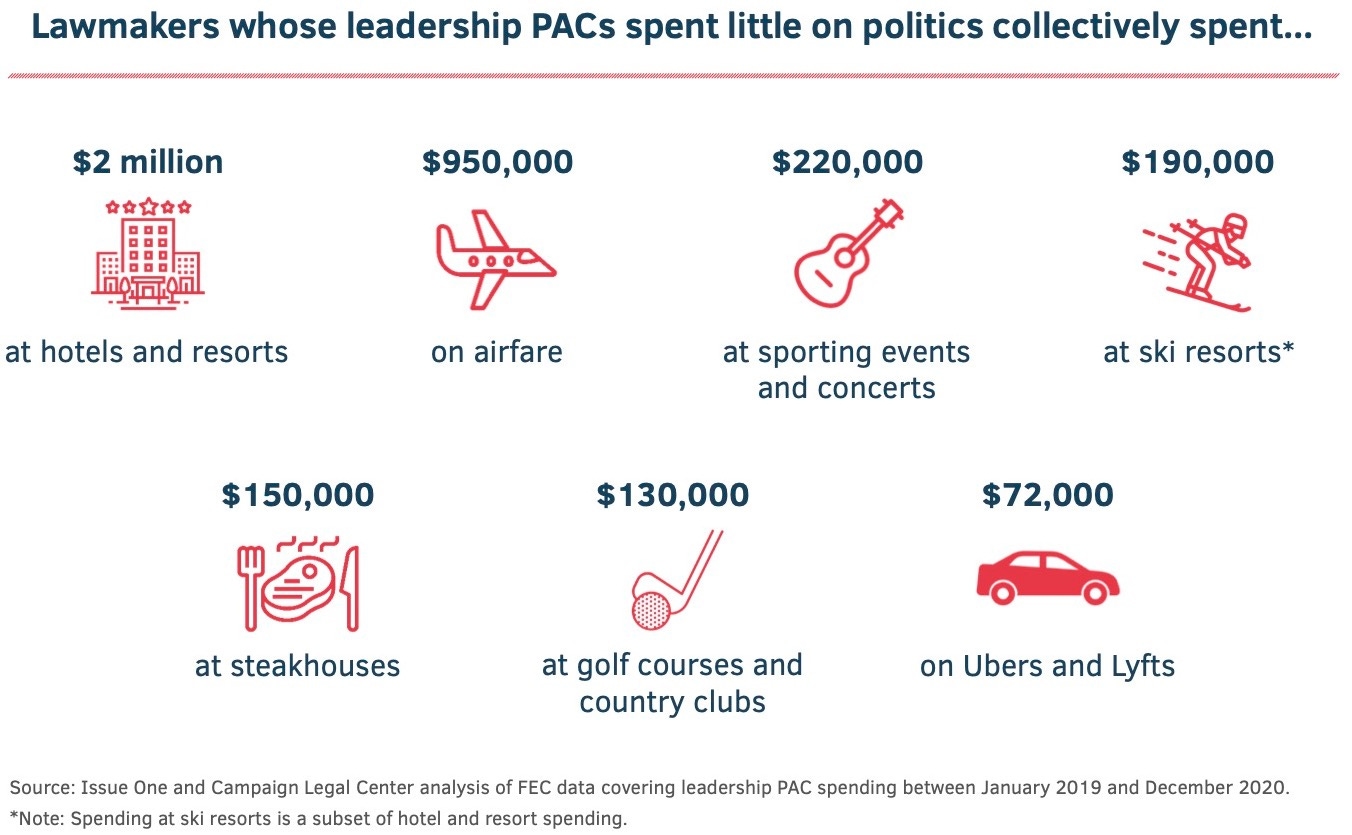

Funding the Good Life

The money raised by leadership PACs is purportedly to fund political activity. But an analysis by Issue One and Campaign Legal Center found that, in 2019-2020, the leadership PACs of 120 members of Congress spent less than half on politics; 43 members’ PACs spent less than 25%. From the analysis:

The report names names and gives details.

Leadership PACs can be used as a personal slush fund.

Where Does the Money Come From?

Well, of the $150M raised mentioned above, the report shows that about 5% comes from small-dollar donors (less than $200), about a third from individuals giving between $200 and $10,000 per PAC5, and

“Roughly 60 percent of this sum has come from political action committies (PACs) connected to companies, trade associations, labor unions and other groups that frequently have business before these lawmakers.”

You might recognize many of the top 15 corporate and labor PAC donors: Honeywell, UPS, AT&T, Northrop Grumman, Nareit, Comcast, Deloitte, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, National Multifamily Housing Council, Home Depot, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, National Air Traffic Controllers Association, National Association of Realtors, and Union Pacific.

You scratch my back; I’ll scratch your back.

Summary

Large sums of money flow through the campaign finance system, with many opportunities for both quid pro quo and a bit of self indulgence.

All of what we’ve discussed thus far is subject to limits and regulation by the FEC, however ineffective.

The Floodgates Open

Hold on for a wild ride: Here we go into the world of unlimited, almost-unregulated campaign finance. Forget the contribution limits chart — it doesn’t apply to anything we’re about to discuss.

Super PACs

With its 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, SCOTUS opened the floodgates of unlimited corporate and union money into politics. Arguing that corporations have First Amendment free speech rights, the Court held that corporations can contribute without limit to independent expenditure-only committees.

Such committees can’t give money to candidate committees and they may not coordinate their spending with candidates — that’s what “independent expenditure” means — but they can collect and disperse unlimited funds in support of issues and candidates. For example, such a committee can run advertisements for or against any candidate or any issue, but may not coordinate those advertisements with a candidate.

Later in 2010, SCOTUS followed up with its ruling in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, allowing unlimited contributions from individuals as well as corporations.

The popular name for such committees is Super PAC. Despite the “PAC” in the name, Super PACs are not governed by FEC limits on donations and the contribution limits chart doesn’t apply.

Super PACs have changed the country’s political landscape: According to OpenSecrets.org, which aggregates data from various disclosures, in the 2020 election cycle the 2,276 Super PACs raised $3.4B, of which they spent $2.1B.

Super PACs outspend candidates in some important races. In 2020, Super PACs outspent candidates in 34 races. In North Carolina, where I live, Super PACs spent $220M in the 2020 NC Senate Race compared to $79M spent by the candidates and parties.

Super PACs enable unlimited political spending in support or opposition to candidates and issues by corporations, unions, and individuals.

If you think that your $1,000 contribution to a candidate has much influence, consider that, in 2020, Sheldon and Miriam Adelson donated $215M to conservative Super PACs and Michael Bloomberg donated $98M to liberal Super PACs. They are #1 and #2 on the list of top individuals funding Super PACs in 20206.

This list is worth skimming. It is also easy to look at other years and to get details of where some of these Super PACs spent their fortunes.

Donations to Super PACs must be disclosed. That’s why we have lists of the big donors, etc. Donations can be obscured by laundering them through LLCs and other structures, but with enough work they can still be understood.

Dark Money

Not so with nonprofit organizations.

Your quaint model of a nonprofit organization might be your church, a charity that fights a dread disease, the local food pantry, or other organizations that help people in myriad ways. You might know that these are governed by section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Other kinds of nonprofits are governed by other parts of section 501(c) of the code. The most important for our discussion are social welfare nonprofits, which are governed by section 501(c)(4) and were intended to promote the social welfare — stuff like volunteer fire departments, Rotary Clubs, etc.

Section 501(c)(4) groups can participate in politics but must spend less than 50% of their money on political activity.

The rest can be used for education, including education about political issues.

There are also 501(c)(5) nonprofits, which are unions, and 501(c)(6) nonprofits, which are business associations like the Chamber of Commerce. Same rules — unlimited contributions and no disclosure of donors.

Can you spell gaping loophole?

Corporations, unions, and individuals can donate to 501(c)(4), 501(c)(5), and 501(c)(6) nonprofits without limit and without disclosure.

IRS enforcement of the limit on political activity is lax.

Does dark money matter? You bet. OpenSecrets.org reports that:

More than half of all TV ads in the 2020 presidential and congressional races were sponsored by dark money sources, as were more than 70% of ads in House and Senate races.

More impressive was the announcement by Charles and David7 Koch in 2015 that they and their network of wealthy compatriots would spend $889 million in the run-up to the 2016 elections. Compare that with the $1.4B raised by Democrats and the $957.6M raised by Republicans for the 2016 election.

Financially, the Koch Brothers network is a party of its own, subject to few rules.

If you want to get an appreciation for the extent that the wielding of dark money has transformed America in the last 50 years, you should read Jane Mayer’s 2016 book Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. Alan Ehrenhalt’s review in The New York Times is a useful introduction.

I also recommend a recent piece in the New York Times Magazine by Jaime Lowe entitledWith ‘Stealth Politics,’ Billionaires Make Sure Their Money Talks, which discusses the disconnect between the way that billionaires talk in public and the way they wield their money in politics.

The Independence Sham

Neither Super PACs nor dark money groups are allowed to coordinate with candidates. How could this possibly be enforced?

Do we know what someone from a PAC and someone from a candidate’s staff discuss over a beer or at one of the many high-stakes political meetings sponsored by Super PACs and dark money sources? Of course not.

A report from the Brennan Center for Justice discusses six ways that coordination is happening, including delaying formal declaration of candidacy to avoid the rules, sharing top aides, candidates raising funds for preferred super PACs, and using common consultants and vendors.

And, just to show how easy it is to evade independence, there’s a new technique that The NY Times reports Democrats around the country are using: Candidates post instructions to their super PACs on public web pages enclosed in little red boxes; the super PACs monitor those pages and follow up on those instructions.

Independence between candidates and super PACs is a (bad) joke.

Current Events

Our campaign finance landscape is big, complicated, murky, dysfunctional, overwhelming, and corrupt.

To make this tangible, I will close with four examples from current events.

Guns

In the wake of the Uvalde massacre, historian Heather Cox Richardson explains that “[t]oday’s insistence that the Second Amendment gives individuals a broad right to own guns comes from two places.”

The first is the National Rifle Association (NRA), an organization formed in 1871 devoted to improving marksmanship and the shooting sport. Until the mid-1970s, its officers “insisted on the right of citizens to own rifles and handguns” but also backed legislation restricting ownership by criminals and mentally ill people, legislation to limit concealed weapons, dealer licensing, and background checks.

The NRA shifted toward opposing gun control in the mid-1970’s, formed a PAC in 1975, and elected a new NRA president who focused on gun rights. This fit well with Movement Conservatism — opposition to business regulation and social welfare — and the NRA endorsed Ronald Reagan. With Reagan elected, Movement Conservatism came to the fore and the NRA became ever more powerful and influential.

The NRA raised prodigious amounts of money — for the time — becoming one of the most powerful lobbies in Washington, spending more than $40M in the 2008 election and more than $50M on Republican candidates in 2016. The NRA spent more on Donald Trump’s election than any other outside group.

According to the Brady Campaign (a 501(c)(4) that fights gun violence), 16 senators in the 116th congress have benefited from more than a million dollars each from the NRA during their political careers, with the top beneficiary, Mitt Romney, receiving $13.6M.

The NRA is not alone. The owners of Daniel Defense, the manufacturer of the weapon used in Uvalde, give heavily to support federal and state candidates opposing limits on access to assault rifles and other semiautomatic weapons.

With the industry’s great success during the pandemic, gun manufacturers have more money than ever for lobbying.

The flow of money from the NRA and gun manufacturers supporting Republican candidates keeps Republican politicians aligned against any attempt to regulate guns.

NC 4th CD Primary

North Carolina’s 4th Congressional District, where I live, is heavily gerrymandered Democratic. Whoever wins the Democratic primary wins the election.

Last month’s primary pitted Valerie Foushee, a 66-year-old African American, left-of-center NC state senator with a long, illustrious history of public service, against Nida Allam, a 28-year-old member of the Durham County Board of Commissioners, and several lesser-known other candidates. It became clear early on that Foushee and Allam were the leading candidates.

Allam is the first Muslim woman to hold public office in North Carolina and is a vocal advocate for Palestinian rights as well as many progressive issues. She was endorsed by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) has long been a pro-Israel organization that supports American politicians who align with their (right wing) views on Israel. According to NC Policy Watch, AIPAC bundled8 more than $430,000 in individual contributions for Foushee. Additionally, AIPAC’s super PAC, called United Democracy Project (UDP), spent $2.1M on Foushee’s behalf. Another super PAC, called Protect Our Future, backed by a crypto billionaire, spent more than $1M supporting Foushee.

A Raleigh News & Observer analysis showed that the total campaign funding of all eight candidates in the race (including Foushee and Allam) was less than the money that the UDP and Protect Our Future super PACs spent on pro-Foushee TV ads and mailers.

Outside money from super PACs can dominate in an election.

The Great Replacement Theory

The so-called great replacement theory (GRT) claims that “elites” (whatever that means) are working to replace America’s white voters with people of color and Jews to achieve political goals. Many violent attacks have been motivated by this conspiracy theory.

You might think that major American corporations would not support politicians who advocate GRT. But you’d be wrong.

Let’s consider support for just one such politician, Elise Stefanik, who is the #3 Republican in the House. Based on research by The Washington Post, 22 large corporations that have made public racial justice pledges have also donated to Stefanik.

An interesting example is UBS, which donated more than $3M to racial justice groups but also donated $17,500 to Stefanik’s campaign and political action committees, even after she was widely criticized for her GRT remarks.

It is impossible to know why these companies make such conflicting donations. I conjecture, however, that large companies feel compelled to donate to powerful politicians who may be able to affect their businesses, even when some of those politicians take positions that are reprehensible to most of the public.

Corporate Stakes in Democracy

Since the Citizens United decision, corporations have been using their newfound influence on politics to advocate for lower taxes, deregulation, and changes in labor law to further reduce worker power. With a few exceptions, they tended to stay out of other political debates, at least publicly.

With the rise of Republican politicians who are working to destroy key aspects of our democracy, including the rule of law, peaceful transfer of power, and election integrity, corporations face a new challenge: Large corporations depend in many ways on a functioning democracy.

Do large corporations use their extensive political power to support politicians who help them in the short term but endanger the core democratic freedoms that make America’s economy work?

Corporations face this dilemma now. The CEOs that comprise the Business Roundtable have, for example, condemned publicly the January 6th insurrection at the Capitol. But, as The Center for Political Accountability’s new report, Practical Stake: Corporations, Political Spending And Democracy, says:

“Leading corporations are pouring millions of their dollars into political spending that ultimately bankrolls the attack on democracy from Washington D.C. to state capitals nationwide.”

For example, the report details complex flows of money that end up supporting members of the House who voted against certifying the 2020 election.

Ultimately, corporations must decide between the short-term benefits they get by supporting politicians who seek to destroy democracy and the long-term harm to the country and themselves they are funding.

Summary

I hope that this too-long discourse has given you a sense for how our system works. Like our tax system, it is staggeringly complex, the better to hide its corruption from most of the public. I hope I’ve opened your eyes to this.

This is my one-sentence summary of what we’ve learned:

Our campaign finance system is engineered to turn money into power without accountability.

Paraphrasing the Jewish sage Hillel, all the rest is commentary9.

What’s Next?

In the newsletter titled Taking Stock, I wrote of four huge, inter-connected foundational threats to American democracy: American oligarchs, corporate wealth and power, economic resentment, and our campaign finance laws.

Having discussed three of these topics, we are now prepared to begin considering some possible win-win solutions. That’s where we’re heading next.

Please join me and invite your friends!

Commissioners are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Commissioners serve staggered six-year terms, with two seats subject to appointment every two years. Occasionally, an independent is appointed, who sides with one party or the other. Lack of a quorum has been a problem.

Prior to 2014, individuals could spend no more than $123,000 on federal candidates in a two-year election cycles. This limit was overturned by the Supreme Court in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission.

Supreme Court of the United States

As SCOTUS issues important decisions with which I disagree, I often find it enlightening to read Justice Kagan’s dissents. She writes clearly and without too much legal jargon.

Since the time period of this study spans two calendar years, it is possible for one individual to donate as much as $10,000.

Sheldon Adelson is now deceased.

Now deceased.

Bundling is when an organization recommends that individuals contribute to certain candidates, collects those contributions, and delivers them to the candidate’s committee. During primary season, AIPAC’s web site listed candidates across the country and collected contributions for those candidates.

A man comes to Hillel asking to be taught the whole Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew bible) while standing on one leg. Hillel says “That which is hateful to you, do not unto another: This is the whole Torah. The rest is commentary — go study.”

Thanks Lee. Hope everyone read this key part about the old $250K limit - "Senator X loaned $260K to his 2018 campaign. He sued to get back the $10K, hoping to overturn the limit. On May 16th, 2022, SCOTUS³ threw out the limit." The Supreme Court opening the door to more money in politics. Sadly the stage is set for more corruption and decline.