Simplifying Taxes to Sustain Democracy

Our current tax system is complicated and opaque, the better to hide many gifts to high earners. Radical simplification would be a first step to a tax system that sustains democracy.

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

We’ve seen in our previous discussions that the high level of inequality that we’ve allowed to develop in the United States threatens the survival of our democracy. We have also seen in the last newsletter issue that the single-minded focus on Adam Smith’s invisible hand metaphor to guide economic policy is fundamentally flawed. To preserve democracy, it must be replaced by a kind of economic pluralism that moves beyond greed-is-good thinking to consider ethics, economic justice, and economic freedom.

As we’ve also seen, our current federal individual income tax system redistributes wealth upward. This helps a few people to become fabulously wealthy and allows the 90-99% to pull away from the rest of us, all at the expense of the bottom 90%. Moreover, our current federal income tax system is a morass of complex special cases, exceptions, and rules that few people understand, but that the upper middle class and above exploit to legally evade taxes.

It is past time for us to fundamentally rethink our federal income tax system so that it is simple, easy-to-understand, inexpensive to administer (relative to our current system, both for the IRS and for individuals), and fair in the sense that it doesn’t redistribute income in a hidden way. This is not to say that we shouldn’t redistribute income, just that income redistribution — to the extent that we want to do it — should be done in a simple, transparent way, not via today’s morass of exemptions and special cases.

Simplicity is the friend of transparency.

So, here’s the plan: In this issue, I’ll outline a simple individual income tax system and explain the many ways in which it is better than our current system. Notably, this system will not, in and of itself, subsidize or penalize specific kinds of economic activity. We’ll no doubt still want to do that. I’ll very briefly discuss that in this newsletter, but will leave most of that discussion to future newsletter issues.

You’re Nuts!

Probably. I recognize that proposing something like this is likely tilting at windmills. But we need to have the conversation about what could be, rather than just discussing adding more complexity — opportunities for more tax avoidance — to an already impossible-for-anyone-to-understand system.

Our Supposedly Progressive Tax System is Effectively Flat

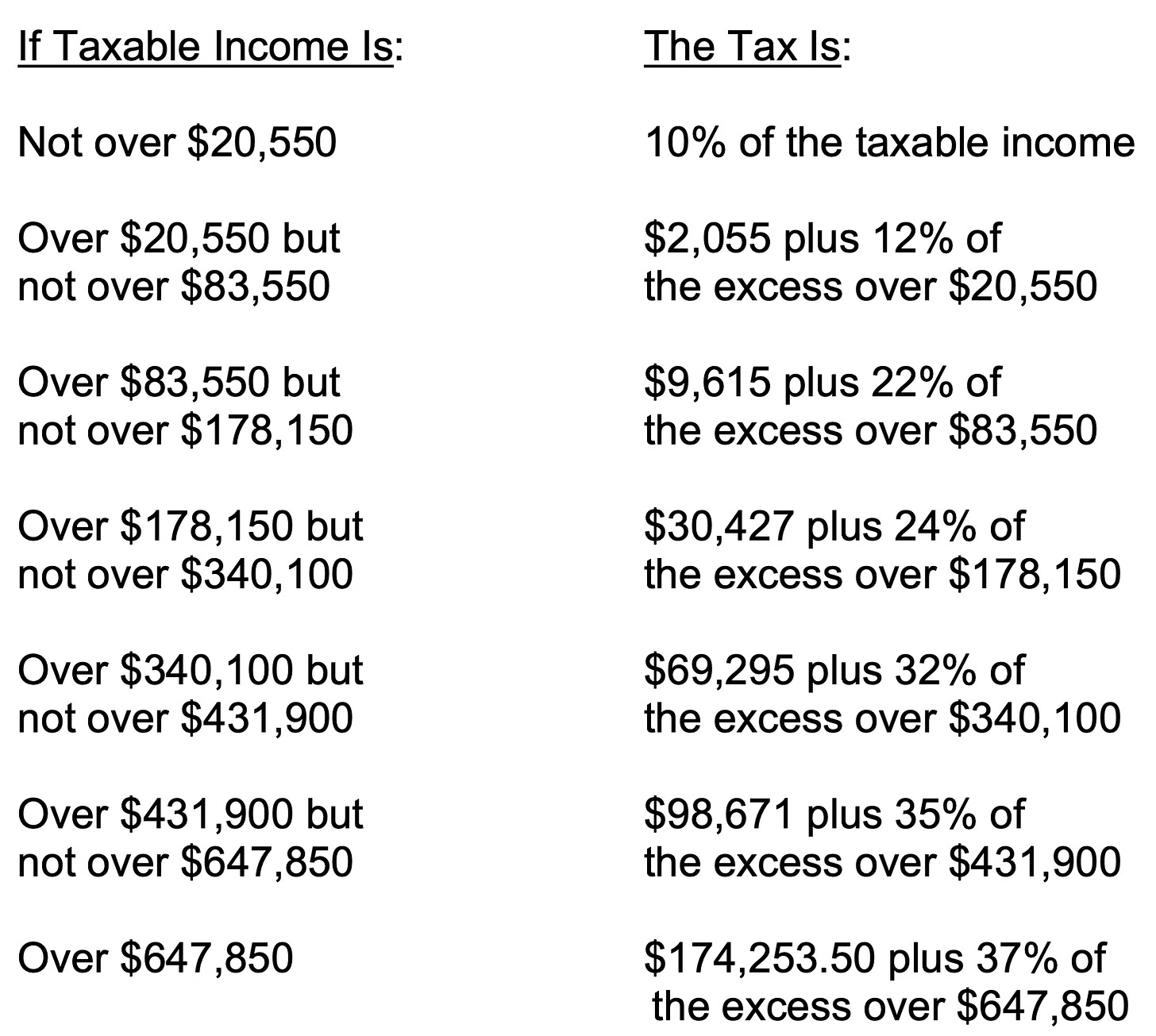

We supposedly have a progressive tax system, one in which higher-earning people pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than lower-earning people. This is usually portrayed by tax rate charts that looks something like this:

The media often say something like “the 35% tax bracket,” but this is misleading for two reasons:

The 35% rate applies only to the portion above the lower limit (i.e., over $431,900). The rate on the income below that lower limit is less, in this case not quite 23%.

Tax brackets apply to income after the many deductions, exceptions, exemptions, and credits that are in the tax code.

Effectively Flat

We tend to forget that both capital gains and dividends are taxed at lower rates than other income, and also that capital gains taxes are deferred. As we’ve discussed previously, deferral of capital gains taxes, coupled with step-up on basis at death, allow some individuals to build vast fortunes that are never taxed.

We also tend to forget about other kinds of taxes, which have significant impact on most people:

Payroll taxes (Medicare and Social Security)

State income tax

State and local property taxes

Consumption taxes

State and local sales taxes

Excise taxes (consumption taxes based on quantity instead of price)

Fees such as car registration, transfer fees, mortgage registration fees, etc.

High earners also get breaks on sales taxes because they spend a relatively greater portion of their income on services, which are mostly not subject to sales tax, than on products, which are mostly subject to sales tax.

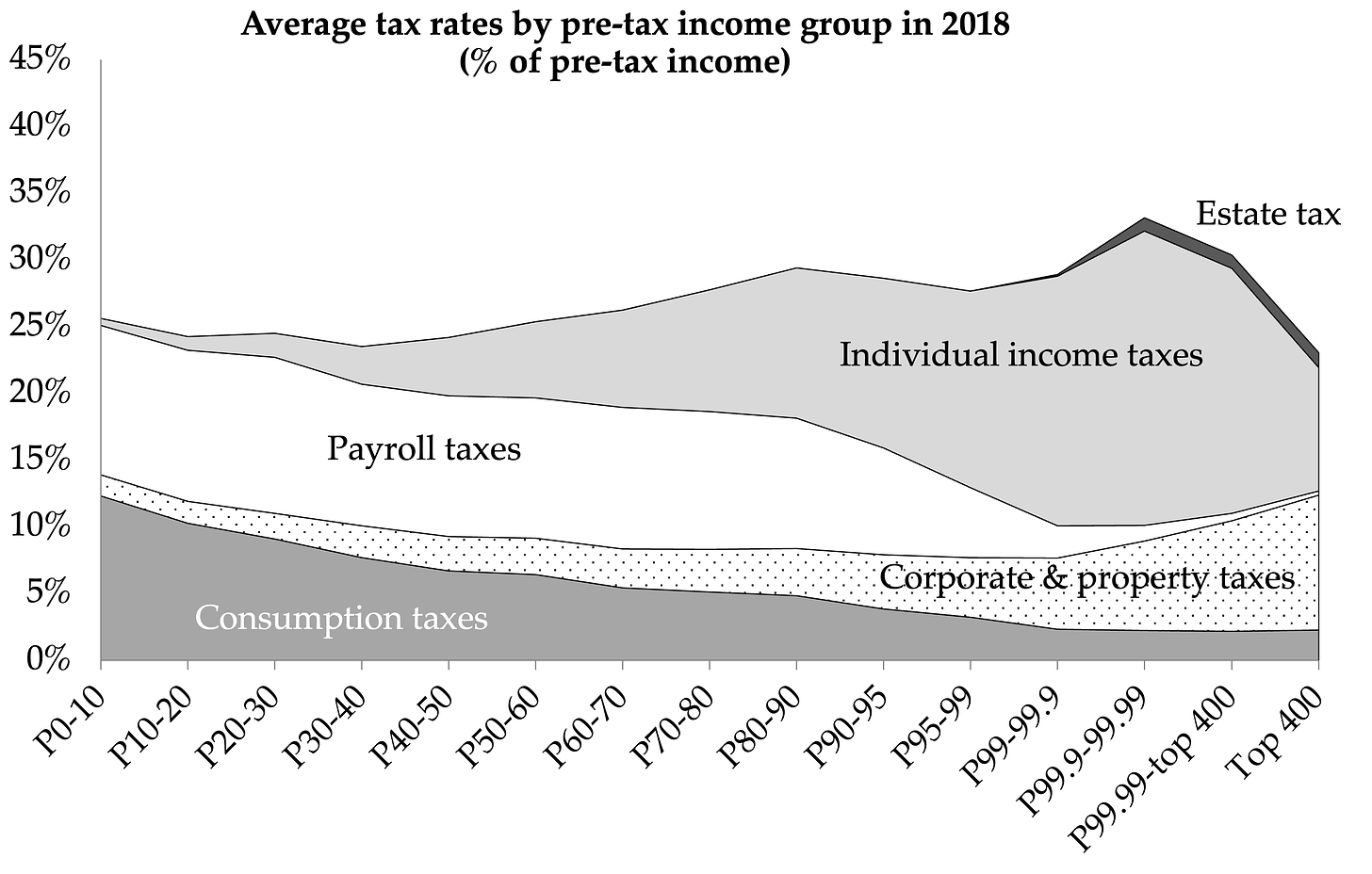

When you put it all together, our tax rates look like this:

The 2018 curve (black) looks almost flat — average at 28% — until you get to above the 99.9 income percentile, when the actually rate goes down.

For most of us, we effectively have a tax system with a flat rate, not the progressive one we’ve been taught we have.

A Regressive Tax System for the Highest Earners

Notice the shocking historical curves (in shades of blue): High-earners have succeeded mightily since the 1950’s in reducing their tax obligations, while the poorest among us are paying an increasingly larger percentage of their income.

What Creates the Effectively Flat Tax System?

Let’s take a deeper look at what creates our effectively-flat tax:

The lowest earners pay almost no income tax. (Remember Mitt Romney’s famous campaign statement about 47% of people not paying taxes? He was correct if the only tax you consider is income tax.) But low earners pay a large percentage of their income in payroll taxes and consumption taxes.

As incomes rise, payroll taxes become an ever-smaller percentage of pre-tax income for higher earners because there is a cap (currently $147,000) on the income on which Social Security taxes are paid. Meanwhile, as earnings rise, payroll taxes decline and income taxes rise, roughly canceling out each other.

Nevertheless, income tax never is as large a percentage of income as one would expect from the tax rate chart. Why? Two reasons. First, the actual rate paid is always lower than the marginal rate shown in the charts. Second, deductions, credits, and preferential treatment of most investment income further reduces the amount of tax higher earners pay.

You may be puzzled to see the corporate and property tax category in this chart. Ultimately the people who own shares of corporations or pay rent are indirectly paying corporate and property taxes, even though a corporation or landlord may send the actual check to the IRS. It doesn’t matter who sends the check — what matters is how those payments affect real people.

As you might imagine, this sort of analysis from the data actually available depends on certain assumptions and methodology choices. Saez and Zucman explain their choices at a high level in their book; more detailed information on their assumptions and methodology is available in the book’s online appendix.

Complexity

Our tax system is exceedingly complex. Planting tongue firmly in cheek: This complexity provides important “benefits.”

Under-the-Radar Gifts to Important Donors and Lobbyists

Congress can provide under-the-radar gifts to important donors and lobbyists in ways that few people will be aware of, much less understand. Examples include: tax benefits for investors in and employees of high-growth companies via special treatment of certain stock options; the carried interest deduction for hedge fund managers; generous treatment of certain real estate transactions; deferred compensation schemes for senior executives; deferral of capital gains and step-up in basis. The list is long.

Creates Big Professional Services Opportunities

A whole industry of tax advisors, tax preparers (including software like Intuit’s TurboTax), and tax planners is built on the complexity of the system. The tax preparation industry in the US was over $11B in 2019 (not including CPAs), with tax advisory services in the US another more than $16B.

Besides all of the people who provide tax-related services, there are a slew of financial planners, lawyers, and accountants who advise their clients on tax-efficient ways to manage their investments, including saving for retirement, saving for children’s educations, saving for medical care, and living during retirement, and, of course, avoiding taxes when passing assets to heirs.

Creates Opportunities for Legal Tax Evasion

Whenever the tax system creates multiple categories of income (ordinary income, long-term capital gains, qualified dividends, etc.), people try to evade taxes by getting as much of their income as possible classified as a kind of income that is taxed at a lower rate. This has long been a problem with our tax system. It seems that whenever “reforms” to the tax system are made, more of these opportunities to evade taxes are created.

The changes made in the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act provide some great examples:

The Act favors so-called pass-through income with a 20% deduction, thus encouraging high-income people to restructure their wage and salary earnings to be pass-through income. There are exceedingly complex (and seemingly arbitrary) rules that determine what income qualifies.

The steep cuts in corporate tax rates invites wealthy individuals to structure their investments as corporations to exploit the lower rates.

The Act includes incentives to shift profits and some operations overseas.

More details are available here.

Keeps the IRS Off Our Backs

The IRS struggles with the implications of our complex tax laws. Creating and enforcing complex rules is itself complicated and expensive, requiring lots of human agents. Automation is hindered. IRS lawyers are outgunned by high-priced lawyers hired by wealthy people and corporations. Similarly, tax courts struggle with the load.

All of this is “great,” because it reduces the number of audits of wealthier people (who have complicated returns) and makes it difficult for the IRS to win cases it does bring.

Reality of Complexity

OK, let me take my tongue out of my cheek:

Tax system complexity is the enemy of transparency and fairness.

Toward a Better Tax System

We’ve established that, taken as a whole, our tax system is, effectively, a complicated, multi-faceted, flat-rate tax system, except for the very highest-income people, where it becomes regressive — extremely high earners pay a lower percentage of their income in taxes than the rest of us. It is also enormously complex, making it difficult for citizens to understand, difficult to determine the magnitude of the tax breaks given and to whom they’re given, difficult for legislators and policy wonks to understand the impact of proposed policy changes, and difficult for the IRS to enforce.

A Simple Flat-RateTax System

Temporarily suspend disbelief and let’s examine a simple flat-rate tax (FRT) system: Everyone pays the same percentage of their income.

When I say income, I mean all income, including unrealized capital gains and implicit income such as your employer paying (part of) your health insurance premiums or contributing to your retirement plan.

In an FRT system, everyone would pay x% of their income in taxes every year, with no deductions or tax credits, no special treatment of certain kinds of income, and no exceptions. Since all income is alike, there would be no benefit trying to game the system by getting income classified one way or the other. This is unlike our current system, in which very high earners arrange their income to be mostly capital gains.

Is it plausible that an FRT system could raise enough revenue to allow the government to run as it currently does? Roughly, what would x have to be?

Answering these questions will take a bit of back-of-the-envelope math. I’ll warn you now that my numbers are very rough estimates based on information from our current, complex system.

Conceptually, however, our approach is straightforward:

Estimate the total income of everyone in the country.

Assume that current tax revenues must be replaced.

Estimate the flat tax rate: Divide current revenues by total income.

Estimating Personal Income

Let’s start with how much income is earned annually. The 2021 numbers from the Bureau of Economic Analysis show that personal income was about $21T, including the following payments that employers make on behalf of employees:

Payments to private pension and profit-sharing plans, government employee retirement plans, private group health and life insurance plans, privately administered workers’ compensation plans, and supplemental unemployment benefit plans.

Payments to government old-age, survivors, and disability insurance; hospital insurance; unemployment insurance, and various other retirement and pension-related programs.

These numbers, however, do not include capital gains, either realized or unrealized. Total realized capital gains in 2018 (the latest data I could find) were $.9T — let’s call it $1T. If we treat realized capital gains as ordinary income, we’d have $22T in personal income.

Of course, to tax all income, we’d also have to tax unrealized capital gains in a manner like we discussed in the July 2nd newsletter, which would add about another (very roughly) $1.8T in income1.

I've ignored the additional dividends or capital gains from increased corporate earnings that would occur if we adopted the proposal I made in the June 18th newsletter.

Since the exact number is not crucial for our plausibility exercise, let’s work with a $24T income figure.

Estimating Revenue Needed

Let’s roughly estimate how much revenue would need to be raised from the FRT system by understanding how much revenue is raised by the current system.

Federal

When we were discussing tax expenditures, we looked at the 2022 federal budget summary, which indicates receipts of $4.4T. The receipts included corporate and individual income taxes, estate and gift taxes, Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes, and about $320B in other miscellaneous revenues. Subtracting those miscellaneous revenues (which do not come from taxes), we’d need it to be able to generate about $4.1T in revenue to meet federal needs.

State and Local Governments

State governments collected $2.2T in revenues in 2019, of which 32% came from transfers from the federal government, implying that the states collected $1.5T in various taxes and fees.

Local governments collected $1.9T in revenues in 2019, of which 34% came from transfers from state and federal governments, implying that local governments collected $1.3T in various taxes and fees.

Estimating the Rate

From a national perspective, to meet federal, state, and local needs, we’d need to generate about $7T in revenue from a flat-rate tax on $24T in personal income. The flat rate needed to do this would be 29%.

Of course, some localities and states that budget higher tax revenues would have higher rates and localities and states that budget lower tax revenues would have lower rates.

Is It Plausible?

An on average flat 29% rate is close to the 28% average actual rate that Saez and Zucman have shown that most people pay under the current system. Let’s look at the big changes:

The payroll taxes, including the regressive Social Security tax, are gone. (All of the revenue currently provided for Social Security would be funded from the flat tax revenue.)

Likewise, regressive consumption taxes are gone, again replaced by revenue from the flat tax.

The benefit of the exclusions and deductions that are in the current tax system would no longer exist, which raises the income on which people are taxed. This mainly affects high-income people, who currently get most of the benefit from tax expenditures. On the other hand, the flat income tax rate is lower than the top marginal rate in the current system. On balance, however, the highest-earning people would pay more than they do currently.

Economics, Ethics, and Policy Issues

If such an FRT system is plausible, is it desirable? In the last newsletter we discussed a framework for thinking about the interaction of economics, ethics, and policy. How does an FRT system fare?

Economic Efficiency and the “Invisible Hand”

Advocates of the keep-the-government-out-of-my-business approach and who believe that the invisible hand brings economic efficiency should love the FRT approach because it eliminates special treatments of income, which, after all, reflect government’s hand on the scale.

Fair Process (also called procedural justice)

The FRT system applies identical rules and rates to all people. It scores strongly on fair process. Additionally, the FRT is transparent, which is crucial for people to believe that they are being treated fairly.

Fair Outcome (also called distributive justice)

The FRT system, as articulated here, makes no attempt to redistribute to ensure desired outcomes, whatever they may be. People who believe that redistribution is important to a healthy society will be unhappy with the FRT.

In particular, liberals who believe strongly in a progressive tax system will dislike this system. I suggest, however, that it is important to compare the FRT, as suggested, to the reality rather than the myth of our current system. Our current system, as we’ve seen is already flat, trending toward regressive at the high income levels.

What Next?

Our current tax system is supposedly a progressive system in which the more you earn the higher the rate you pay. We’ve seen that this is a false myth. We’ve also discussed the complexity of our current system and why this is a problem.

We’ve then introduced a flat-rate tax system that is simple, fits well with the invisible hand metaphor and the notion of economic efficiency, and provides fair process.

The flat-rate tax system, however, doesn’t redistribute wealth to attempt to create desired outcomes (food and shelter, education, etc.). It also does not incentivize economic behaviors that we, as a society, might want to encourage.

In keeping with the economic pluralism approach we discussed in the last issue, the next newsletter issue will delve into possible approaches for providing desirable outcomes while maintaining the benefits of the FRT system. For example, we’ll discuss ways to reintroduce subsidies for housing but to do so in a way that helps the poor as much as it helps the middle and upper classes.

I also plan to discuss the advantage of the FRT-based approach over the wealth tax that has been advocated by various economists and Democratic politicians.

Estimating how much additional income would come from taxing unrealized capital gains is extremely difficult and depends on many details. Estimates have been made based on data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, which samples, among many other things, the amount of unrealized capital gains families have.

Using this data, Batchelder and Kamin have estimated that taxing unrealized gains, using a scheme something like what I described previously, would raise $4.4T in additional tax revenues over 10 years. That estimate assumes that the gains would be taxed using the existing marginal tax rates. Since most unrealized gains are held by high-income families, let’s assume that those gains would have been taxed at a 23.8% marginal rate in their estimation (i.e., 20% capital gains tax plus 3.8% net investment income tax), implying that the actual capital gains being taxed would be $18.5T over ten years, or $1.8T per year.

Recognizing that this is an unreliable estimate, add $1.8T to our estimate of annual personal income.

What I object to the most is the intrusiveness of the IRS. Every single financial transaction one makes nowadays is tracked and recorded. If we could even collect the same amount of taxes without this tracking I would prefer that. Which is why I was in favor the Fairtax years ago. It is a consumption-based tax instead of an income-based tax. It is still intrusive in the sense that companies now are the tax collectors instead of the IRS; but they already are in order to collect state sales taxes (even across states now). Which is still better than every single resident. See https://reason.com/2023/01/13/whatever-the-fate-of-the-fair-tax-act-congress-should-still-abolish-the-irs/

I teach the tax rules regarding real estate and income and capital gains tax. Even this little section of tax law is confusing for my students who, I believe, represent mainstream Americans in terms of their general education and math abilities.

. The one area of real estate tax law that has changed significantly in the last few years is the limit on deductions for mortgage interest and state and local taxes. The decrease in deductibility of these items presumably hurt those Americans who are borrowing large sums to buy/build their first homes. I believe that this change was targeted to hurt wealthier Americans who live in high-cost areas (New York, California, urban areas such as Chicago, etc.) that tend to lean toward voting Democratic rather than Republican. Am I wrong?

The idea of the flat tax is very appealing to me! Thanks for the overwhelming and astounding research, Lee.