Subsidies

Starting from a simple flat-rate tax system, we discuss how to create subsidies that help people who need help, not high-earners who don't need help.

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

Last time, I discussed our mishmash of income taxes with rates obfuscated by deductions and special treatment of certain categories of income, together with payroll taxes and a variety of state and local taxes, all with their own special rules and categories. We are told that we have a progressive tax system, where high earners pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than low earners.

The data show that this is a myth: Under our mishmash tax system almost everyone pays roughly the same percentage of their income — except the very top earners, who pay less.

We might as well replace our complicated, opaque mishmash with a simple flat-rate tax (FRT) where everyone really pays the same percentage of all of their income. Some people would perceive this as fair because everyone is treated identically. Others would perceive this as unfair because they believe that low-income people ought to pay less than higher-income people.

We can trade off between these two perceptions by introducing subsidies into the system, replacing our current system’s dizzying array of deductions, multiple kinds of credits, and special treatments of certain income with a simple approach to subsidies that is easy to understand and allows us to help lower-income people should we choose to do so.

Here’s the plan: I’ll first discuss the general approach to providing subsidies, then illustrate it with two specific examples, contrasting it with what we do now. I’ll then conclude with an analysis of the win-win aspects of the resulting tax system.

Subsidies in the Current System

In our current tax system, we use multiple approaches to subsidize certain economic activities or to help certain people. Before we discuss how to introduce subsidies into the proposed FRT system, let’s understand the breadth, complexity, and scope of subsidies in the current system.

Income Tax Deductions

A deduction reduces the amount of income that is taxed. A simple example is a deduction for being 65+ years old, which reduces an individual’s income by $1,400. What does this subsidize? I don’t know; I’d guess it is a holdover from the days when being old typically meant being poor.

How does this benefit the taxpayer? If your marginal tax rate is 37% (individual income over $539,900), this deduction saves you $518 in taxes; if your marginal tax rate is 10% (individual income $10,275 or less), this deduction save you $140 in taxes. I guess being old while earning a lot sucks more than being old and earning a little, so the deduction is worth more. Seriously, this makes no sense.

But this is a general characteristic of income tax deductions:

A deduction of a given amount helps higher earners more than lower earners.

So, whenever you see a deduction, ask: Why are we subsidizing higher earners more than lower earners with this deduction?

In fact, our system magnifies this effect by offering deductions for which no low earner will qualify. More on this later.

Important examples include the standard deduction (everyone can get it), contribution to traditional IRA plan deduction, charitable contribution deduction, mortgage interest deduction, qualified business income deduction, and state and local tax deduction.

Income Tax Credits

A credit directly decreases your tax bill. If you qualify for, say, a $1,000 tax credit, your tax bill is reduced by $1,000, regardless of your income level. Well, maybe: If you don’t owe $1,000 of taxes, then how can your tax bill be reduced by $1,000?

There are two types of credits: refundable and non-refundable. If the credit is refundable, the IRS will send you a refund. If you otherwise owe $600 in taxes but qualify for a $1,000 refundable tax credit, you’ll get a $400 refund. If the credit is non-refundable, you either don’t get that $400 or, in limited cases, you can carry it forward to use in a future year (possibly with a time limit).

Refundable tax credits are equally valuable to low earners and high earners.

Non-refundable tax credits are often of less value to low earners because their income tax obligations are already low.

Important examples include a child tax credit (available to parents under certain conditions; refundable), a premium tax credit (subsidizes premiums for health insurance obtained through Obamacare marketplaces; refundable), the earned-income tax credit (available to low-income workers, especially those with children; refundable), and lifetime learning credit (subsidizes tuition and other education expenses for individuals who earn less than $69,000; non-refundable).

Exclusion of Certain Income

Certain income is excluded from income taxes as if this income doesn’t exist. It isn’t taxed and it doesn’t affect which tax bracket you’re in.

There are many exclusions. Important examples include employment-based health insurance (your employer pays the premium for your health insurance), your and your employer’s contributions to a traditional 401k retirement plan, the capital gains of assets transferred at death, capital gains on the sale of residences, and social security benefits (subject to income limits).

Preferential Treatment of Certain Income

As we’ve extensively discussed previously, capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income and, importantly, taxes are deferred until gains are realized. Dividends are also taxed at a lower rate but not deferred.

Scale of the Subsidies

The subsidies provided by the major tax expenditures identified in the Congressional Budget Office’s report amounted to $1.2T in 2019. For perspective, the 2019 federal budget was about $5T and the deficit was a bit under $1T.

We provide huge subsidies through tax breaks of various kinds.

Distribution of the Subsidies

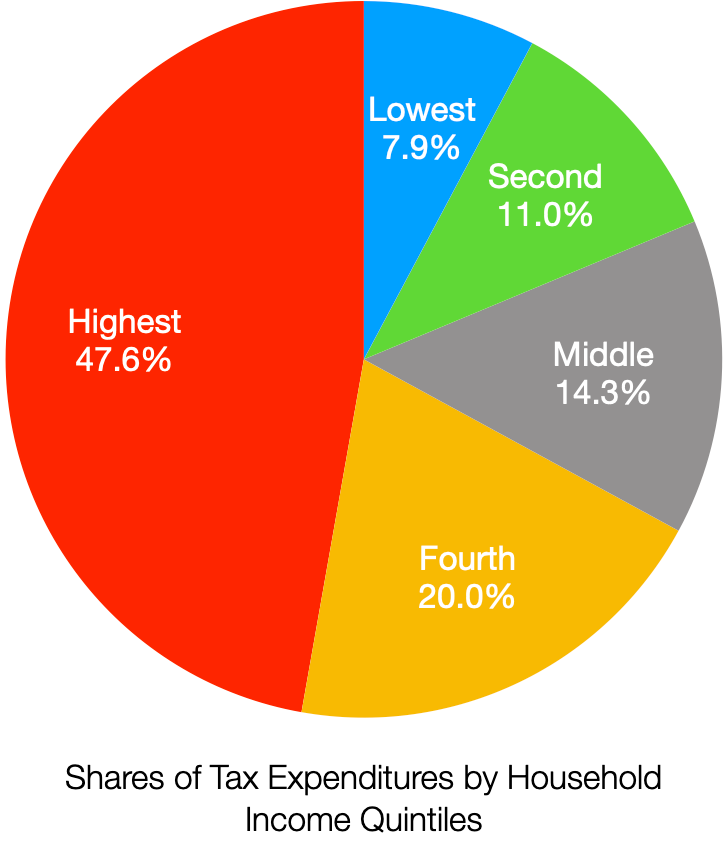

Moreover, the benefit of these tax breaks is distributed mostly to people who need it least1:

Nearly half of the benefit of these tax breaks flows to the 20% highest-earning households. Less than 8% of the benefit of these tax breaks flows to the 20% lowest-earning households.

Looking at the chart, we can also see clearly that

Our subsidies are regressive: The more you earn, the more we spend subsidizing you.

Why Are Our Subsidies So Regressive?

Why are we spending so much to subsidize the highest earners among us while spending so little to subsidize the people who are struggling?

I can only offer my personal opinion:

The wealthy and the powerful have worked for at least 50 years to lower their own tax burden, despite being blessed with tremendous financial resources.

They’ve been helped by politicians and others who have espoused greed-is-good, trickle-down economic theories, and by extensive lobbying and large campaign contributions. They’ve been helped by those politicians and others who encourage us to resent helping “those lazy, poor people”. They’ve been helped by those who preach a brand of selfishness that says that “I’m a self-made man2 who struggled and made it on my own without help from anyone” (even though that’s never true), and therfore everyone else should manage to do the same without a helping hand.

They’ve been helped by those who suggest that the economic pie we share is fixed, so I better grab all that I can, when, in fact, working together we can grow the pie for the benefit of all of us.

And — this is crucial — they’ve been helped by the complexity of our tax code, which makes it easy to hide large tax breaks for high earners while at the same time help for low earners is highlighted and denigrated. In my experience, talking to friends and relatives, few even highly-educated people understand how our tax system works and the benefits it delivers to high earners.

Re-envisioning Subsidies for the FRT

The flat-rate tax (FRT) I proposed last time would solve the hiding-in-complexity problem and give us a fair base to from which to start, fair in the sense that everyone pays the same fraction of their income in taxes.

If we want to subsidize certain behaviors or help certain groups of people — and I believe that we should do both — we can do it in a way that is perceived to be fair in its outcomes: We should help people who need helping. Doing so would address the valid criticism that the FRT is not progressive.

Let’s look at a few examples and then draw some principles from those examples.

Legally Blind

Let’s warm up with something pretty simple: Since 1943, people who are legally blind have been able to take a tax deduction, currently $1400 or $1750 depending on your living arrangement. As we discussed above, this tax deduction is worth more to higher-income people than to lower-income people. It is hard to imagine that we think higher-income blind people need or deserve more assistance than lower-income blind people, but that’s what we do currently.

It would make more sense to just give any blind person a tax-free fixed subsidy payment, say, for argument’s sake, $1,000.

Some low-income people would likely find it helpful to receive the subsidy during the course of the year rather than having to wait for “tax time”. In the good old days of paper checks and the like, administering subsidies through the income tax system reduced administrative overhead. But these days, the subsidy could be paid through electronic funds transfer with little overhead and people could have it when the really need it without having to pay for loans to hold them over to tax time.

Pay subsidies on an ongoing basis rather than tying them to “tax time.”

This subsidy is simple in that clear criteria have been established and everyone eligible gets the subsidy. It is also relatively easy to predict how much the subsidy will cost the government.

Now let’s consider the impact of this subsidy on the taxpayer’s financial situation. A $1,000 subsidy given to someone earning $1M is an increase of .1% — it has negligible impact on that person. The same $1,000 subsidy given to someone earning $25,000 is a 4% increase in earnings, enough to matter in that person’s financial life.

Fixed-amount subsidies (instead of deductions) makes the tax+subsidy system both more progressive and more logical.

Home Mortgage Interest

Let’s take on a much more complex example.

Current Tax System

In our current system, we subsidize the purchase of homes by allowing the interest on a home mortgage to be deducted from one’s income taxes. The full rules are somewhat complex, with IRS Publication 936, the relevant IRS booklet taking 19 pages.

For our purposes, I’ll boil it down to its essence: If you have a loan secured by your qualified home, you can deduct the annual interest you pay on that loan, up to the interest on $750,000 of debt. The limit is $1M for loans secured prior to December 16, 2017 and there’s no limit for loans secured prior to October 13, 1987.

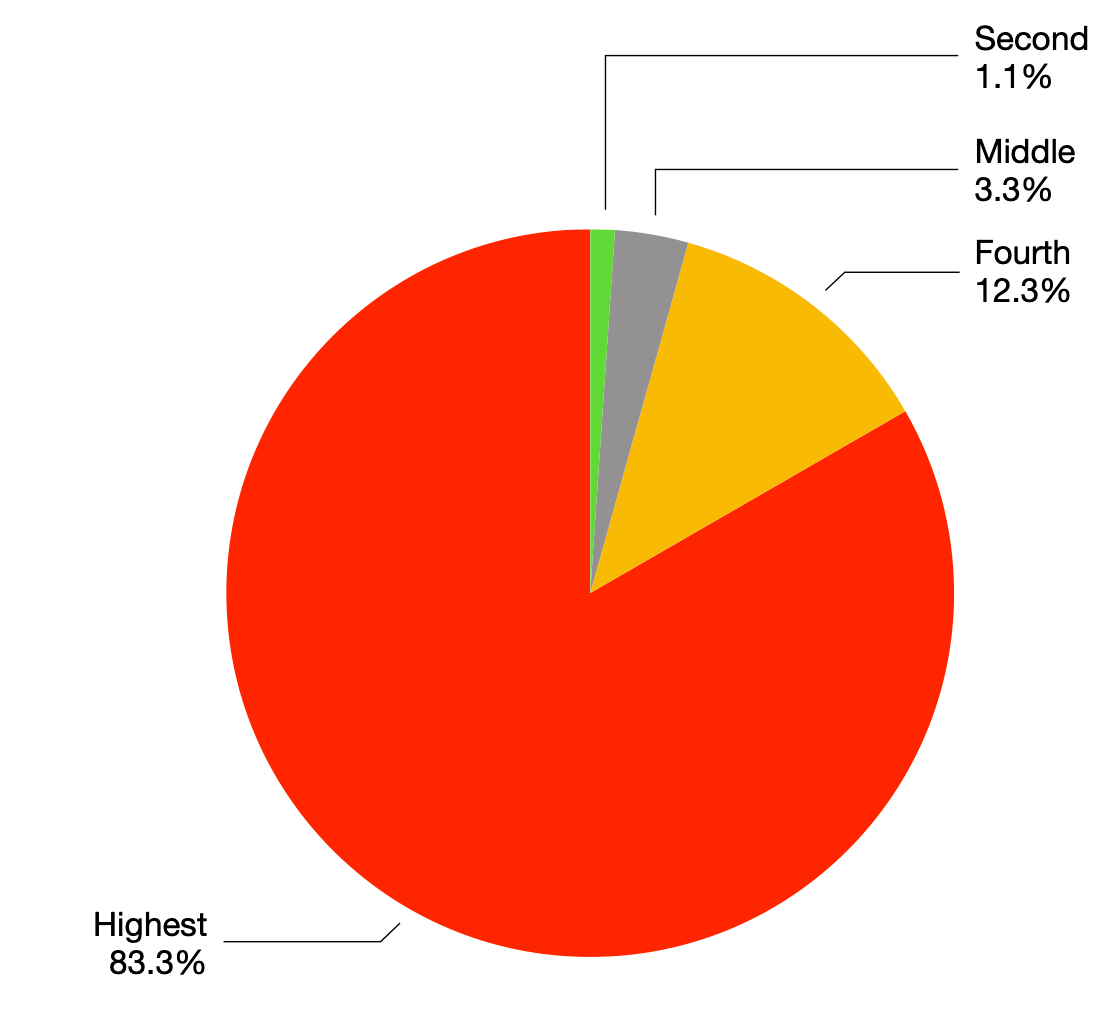

The benefit of the 2019 income tax expenditure for this deduction was $28B, distributed among the income quintiles like this3:

So, 83% of the benefit of this deduction goes to households in the top quintile of income. Why? There are a few reasons:

To qualify for the deduction, you have to be able to afford to buy your own home.

Furthermore, even if you qualify for this deduction, as a lower earner your standard deduction might be larger than the total of all your itemized deductions (like this one), making it better to claim the standard deduction.

The bottom line is:

The vast majority of the benefit of the current mortgage interest deduction goes to households in the top income quintile.

Again, we should ask why we do this. I can think of a few possibilities:

Culture and History

Home ownership is part of the “American Dream” so we subsidize it.

Before the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), many more people in the third and fourth quintiles itemized deductions, allowing them to benefit from the mortgage interest deduction. (Statistics on who itemizes pre- and post-TCJA are available here.) The TCJA was poorly designed and its authors either failed to recognize that we are now primarily subsidizing just top earners, didn’t care that we are only subsidizing top earners, or intended that we only subsidize top earners.

This deduction is not just about helping families. It could be argued that the deduction allows banks to profit from charging higher mortgage rates than the market would otherwise bear.

Similarly, it could be argued that the mortgage deduction helps the construction industry and its supply chain, and the real estate industry. It is not clear, however, that the deduction in its current form subsidizes many people who would not otherwise be able to buy/build essentially the same homes.

Reframing

Everybody needs shelter. Reframing the subsidy as subsidizing shelter rather than subsidizing mortgage interest makes it clear that the pie chart above is not at all what we would want. Top earners can afford very nice shelter without subsidies — thank you very much.

You’d think that if we want to subsidize shelter, we’d start with helping low earners not high earners.

Indeed, we have a totally separate system for low-income housing run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), in conjunction with state and local governments. It is officially called the Housing Choice Vouchers Program or, more commonly, Section 8 housing. According to a report from the Urban Institute, in 2019 the federal government spent $51B on housing assistance.

Section 8 housing has been an abject failure on many levels. I can’t go into all the reasons here, but you can find a good summary in the article How Housing Policy is Failing Poor Americans.

Part of the problem, in my opinion, is that Section 8 places onerous constraints on the people it is trying to support, restricting the places in which they can live, and making them wait on long lists for eligible housing. It stigmatizes them by making them pay for part of their rent with vouchers. Landlords don’t like the bureaucracy associated with the program and often corral Section 8 renters into poor quality housing in low-income ghettos.

Contrast this with how the mortgage subsidy is implemented: Your mortgage lender sends a Form 1098 to the IRS and to you, you enter the reported interest on Schedule A of your tax return and you’re done4. There's no restriction on what kind of home you purchase or where it is located. There's no stigma attached to using the deduction so receiving the subsidy doesn’t make it harder to buy a home.

When helping low earners get shelter, we restrict them, delay them, and stigmatize them; when helping high earners get shelter, we are flexible and make it easy.

A Better Approach

We’re spending a lot of money helping poor people and rich people get shelter but little for people in the middle. Let’s get a sense for the total in 2019:

$28B in tax expenditures for the mortgage interest deduction. As we’ve seen, almost all of this helps people in the top quintile.

$51B on federal direct housing assistance. (The amount increased substantially in 2021 as a result of Covid-related initiatives.) This helps low-income people.

$35B in tax expenditures from excluding capital gains on the sale of a primary residence5. This helps primarily people in the top two quintiles.

This totals to $114B in 2019, and has gone much higher in 2021.

Suppose that we repurpose this money, perhaps more or perhaps less, depending on the country’s economic circumstances and political mood, and do the following:

Phase out subsidizing high-income people for housing.

Phase out Section 8 housing.

Subsidize low-income people with a direct monthly payment to use toward shelter. Make it simple: no criteria for what they pay in rent, where they live, or whether they rent or buy. Treat the recipients like adults and give them the freedom to spend the subsidy on shelter as they see fit. Landlords needn’t know whether or not someone is getting a subsidy.

Let’s assume that we have $120B to work with and do some very rough calculations just to see the possibilities and do a sanity check. Note: I’m definitely not trying to design a program here.

The Census Bureau reports that median rent in the country is $1100 per month (likely higher now). Suppose we wanted to provide a subsidy of a third of the median rent to every household, which would be $367 per month. Spending $120B, we could provide that subsidy to about 27 million households, out of about 122 million total households. That would cover about 22% of the lowest-income households, or approximately the first quintile.

Compare this to Section 8, which provides assistance to 4.8 million households. Of course, we could adjust the numbers to provide larger/smaller subsidies to fewer/more households or spend more money to provide larger subsidies or cover more people. We’d probably want subsidies to be phased out gradually as income rises so that there are no cliffs.

The point is that by focusing our spending on people who need the help and not on high-income people, and implementing a program that is simple, treats recipients with respect and allows them to make choices that are good for them, and doesn’t stigmatize recipients of the subsidies, we can probably do a better job helping more people better.

A Pattern

Is there a pattern we can follow as we design subsidies? I think that there is. And it is pretty simple:

Subsidize people who need help, not people who are high-income. Use gradual phaseouts of eligibility by income rather than sharp cliffs.

Use the money formerly devoted to tax expenditures for high-income people to fund subsidies for low-income people.

Frame subsidies based on broad goals, not narrow approaches that leave low-income people out. Examples: subsidize shelter not owning houses; subsidize purchase of clean energy not just solar panels on rooftops.

Design programs that are simple and treat recipients with respect by not imposing onerous rules, restrictions, and processes.

Treat recipients as the adults they are by allowing them the freedom to make their own decisions about what is best for them. We do this by giving them money and letting them choose how to spend the money within the category of good or service we’re subsidizing.

Don’t stigmatize recipients to landlords and other vendors or service providers by forcing them to use vouchers or other restricted means of paying for what they receive. A subsidy program should not do unto low-income people what it wouldn’t do unto high-income people.

Effect on Inequality

A valid critique of a flat-rate tax system is that everyone pays the same percentage of their income in taxes. But that’s the same reason that some other people consider this a fair way to tax people and particularly like the fact that everyone pays.

Like most liberals, I’ve always supported a progressive income tax system in which low earners pay a smaller percentage of their income than do high earners. But when I came to understand that our system being progressive is just a myth, not a reality, I came to see the value of a flat-rate tax as a way to both simplify and to stop the lying about the reality of our system.

However, many of us, including me, also believe that we, as a society, should help people who need help to achieve a certain standard of living and the opportunity to grow and improve. We, as a society, can do this by subsidizing what we think is important.

Implemented as I’ve described above, subsidies do this by funding lower-income people instead of the way that our current subsidies predominately fund higher-income people. For low-income people a relatively small subsidy can have a large impact on their life. To someone earning $20K per year, a $4400 annual shelter subsidy would increase their effective income by 22%. This is a big deal. To someone earning $1M, not getting the same subsidy is inconsequential, less than a half percent.

Subsidies given to lower-income people and not to higher-income people have a disproportionally large positive impact on the recipients and a much smaller negative impact on non-recipients. Crucially, we subsidize with money, not with tax breaks hidden by the complexity and opaqueness of our tax system.

Taxes become a way of funding our common government. Subsidies become a way for society to help people who need help.

Why is this a Win-Win Approach?

Conservatives have long argued that everyone should bear the same tax burden and thus there have been many conservative advocates of a flat-tax approach. Liberals advocate for progressive tax systems where tax rates increase with earnings.

Both conservative and liberal politicians are disingenuous because they both want to keep the complex set of rules, deductions, and credits that plague our existing system. For example, liberals have recently advocated to restore full deductions for state and local taxes that were limited by the TCJA, despite the fact that these deductions are highly regressive, helping high-income people but not low-income people. And conservatives have recently introduced (in the TCJA) new deductions that lower taxes on high-income people.

The approach I’ve articulated here creates two separate discussions: taxes and subsidies. On taxes, it takes an approach conservatives have liked, but it removes the disingenuous parts. On subsidies, it takes an approach that liberals have liked, but also removes the disingenuous parts. Moreover, the approach I’ve articulated aims for simplicity and the transparency that results from simplicity. I believe that politicians of all persuasions would be forced to have more honest conversations with their constituents if more people were able to understand the reality of our systems.

These statements are from calculations I made using the data behind Figure 5 in the CBO’s report. The data are available here.

Sorry ladies, I’ve never heard or read of a women saying this.

It is a bit more complicated if you rent out your second home for some of the time. If you have more than two homes, you’re out of luck — you can only do the mortgage interest deduction for two homes.

From the aforementioned CBO report.

Lee, this discussion is so clear and your solutions so obvious that I am sharing this article with my real estate students and others. Thank you!

Some very good points in your analysis, Lee. Some additional points might be considered. First, there are at least two alternatives to your proposal for subsidies. One is to replace most (but not all) existing subsidies with a Universal Basic Income that is income tax financed. This could produce a progressive overall incidence (taxes and subsidies combined). A different but similar alternative is to use a refundable Negative Income Tax (a la Friedman), which is politically more feasible than a UBI because it has lower revenue requirements to finance it. Second, I agree that it makes no sense to tax capital gains at a different rate than other income; however, fairly long-term nominal gains can represent much lower real (inflation-adjusted) capital gains. If, for example, a person owned an asset that appreciated at exactly the same rate as inflation, they would have a tax obligation on an asset that had not appreciated at all in real terms -- since it's nominal gains that are taxed. This also makes no sense. A solution would be to deflate the gains with a price index for purposes of taxation.