Weaponizing Religious Freedom

A well-organized, well-funded effort is underway to interpret religious freedom as a weapon that can be used to impose beliefs on others.

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

Today’s Supreme Court is at the vanguard of applying doublespeak to advance a conservative vision of Christianity as the nation’s religion.

Building on last issue’s discussion of religious freedom, in this and the next several issues of the newsletter, I will explain that our freedom of religion in the United States is under steady attack and is yielding — slowly at first, quickly now — to that attack. The recent decision to overturn Roe v. Wade is the the latest — and most significant — result of this attack.

The actors are many but the crucial accelerant is that six of the Supreme Court’s justices — the euphemistically-named pro-religious-freedom majority that Mike Pence bragged about — are on board with the program. These six justices were all appointed by Republican presidents; they are all conservative Christians; five of these six justices were appointed by presidents who lost the popular vote.

To understand how we got here, we need to go back to a case from 30 years ago that should have resulted in a simple ruling of narrow scope. Instead, Justice Scalia wrote a majority opinion that provoked an outcry and then a reaction from Congress. That’s where we’ll start. In that discussion, I continue to be guided by Andrew Seidel’s book American Crusade: How the Supreme Court is Weaponizing Religious Freedom.

Setting the Stage

The 1990 Supreme Court decision in Employment Division v. Smith led to the passage in 1993 of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

Two men, Al Smith and Galen Black, were fired by their employer, a private, Oregon-based drug rehabilitation organization that prohibited employees from using alcohol and illegal drugs. After they used peyote at Native American religious ceremonies, they were fired “for cause,” that is, for violating their employer’s drug policy. Having been fired for cause, Oregon’s Employment Division denied them unemployment benefits.

Smith and Black each sued the Employment Division, claiming that their religious freedom had been violated because they were fired for using peyote in a religious ritual1. In fact, they were fired for violating their employer’s policy, which would have applied to using any illegal drug.

The government didn’t infringe on their religious freedom; it was their employer, a private organization, that prohibited the drug use and fired them for it. Oregon denied their unemployment benefits as they would in any firing for cause.

The Supreme Court reviewed their case (now combined into a single case) and ruled — correctly — that the benefits were denied for violating the employer’s policy. Religion had nothing to do with the case.

Nevertheless, Justice Scalia, writing for the majority, expounded on religious freedom and its limits:

The free exercise of religion means, first and foremost, the right to believe and profess whatever religious doctrine one desires. Thus, the First Amendment obviously excludes all "governmental regulation of religious beliefs as such."

…

But the "exercise of religion" often involves not only belief and profession but the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts: assembling with others for a worship service, participating in sacramental use of bread and wine, proselytizing, abstaining from certain foods or certain modes of transportation. It would be true, we think (though no case of ours has involved the point), that a state would be "prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]" if it sought to ban such acts or abstentions only when they are engaged in for religious reasons, or only because of the religious belief that they display. It would doubtless be unconstitutional, for example, to ban the casting of "statues that are to be used for worship purposes," or to prohibit bowing down before a golden calf.

Respondents in the present case, however, seek to carry the meaning of "prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]" one large step further. They contend that their religious motivation for using peyote places them beyond the reach of a criminal law that is not specifically directed at their religious practice, and that is concededly constitutional as applied to those who use the drug for other reasons. They assert, in other words, that "prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]" includes requiring any individual to observe a generally applicable law that requires (or forbids) the performance of an act that his religious belief forbids (or requires). As a textual matter, we do not think the words must be given that meaning.

…

We have never held that an individual's religious beliefs excuse him from compliance with an otherwise valid law prohibiting conduct that the State is free to regulate. On the contrary, the record of more than a century of our free exercise jurisprudence contradicts that proposition.

Put succinctly, Scalia’s opinion defended Lines #1 and #2 (if this doesn’t mean anything to you, please read this from the last newsletter). There was no need for him to do this because the case was really about violating conditions of employment, not about freedom of religion. But he did it.

So far, so good, albeit unnecessary. The, however, he concluded his opinion with this (emphasis mine):

It may fairly be said that leaving accommodation to the political process will place at a relative disadvantage those religious practices that are not widely engaged in; but that unavoidable consequence of democratic government must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself or in which judges weigh the social importance of all laws against the centrality of all religious beliefs.

In other words, in deciding which religious practices are accommodated, minority religions should expect to lose.

Justice O’Connor, agreeing with the outcome but not the rationale, wrote:

Although I agree with the result the Court reaches in this case, I cannot join its opinion. In my view, today's holding dramatically departs from well-settled First Amendment jurisprudence, appears unnecessary to resolve the question presented, and is incompatible with our Nation's fundamental commitment to individual religious liberty.

Scalia’s opinion set off a firestorm of requests by both conservative and liberal organizations, religious minorities, mainstream religious organizations, and legal experts for a rehearing. As Oliver Thomas, general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs put it: “'I seriously doubt that these groups have ever been in the same room together'' adding that they all agreed that the opinion was ''disastrous for the free exercise of religion.''

On June 4, 1990, the Supreme Court denied a rehearing of the case.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act

Congress took up Scalia’s challenge. Senator Ted Kennedy sponsored the Senate version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). When Senator Joe Biden introduced the act before the Senate, he said:

“A rule announced in a recent Supreme Court opinion, Employment Division versus Smith, could lead to unnecessary restrictions on religious freedom. …

Today I am introducing legislation to restore the previous rule of law, which required the Government to justify restrictions on religious freedom. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1990 would allow Government to restrict religious freedom only if the restriction is a general law that does not intentionally discriminate against religion. The Government will also have to show a compelling State interest in enforcing the law and that it has chosen the least restrictive way to further its interest.”

Representative Charles Schumer introduced the House version. The Act passed the House unanimously and only three Senators voted against it. President Bill Clinton signed it.

So, what did RFRA restore? The Act itself tells us:

"to restore the compelling interest test as set forth in Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) and Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) and to guarantee its application in all cases where free exercise of religion is burdened”

The Sherbert case established the compelling interest test. The test arose out of a case in which Adele Sherbert, who had recently become a Seventh Day Adventist, was required by her long-time employer to work a six-day week. Since South Carolina’s law prohibited manufacturing activity on Sundays (because it is the “Lord’s Day”) and her religion observes a Sabbath day on Saturday, it was impossible for her to work a six-day week. She was fired and denied unemployment compensation.

The Supreme Court ruled that denying her unemployment compensation imposed a substantial burden on her exercise of religious freedom. In doing so, they established the Sherbert Test, which requires “demonstration of such a compelling interest and narrow tailoring in all Free Exercise cases in which a religious person was substantially burdened by a law”.

RFRA restored this test as the way courts would determine whether a government action unduly burdened someone’s free exercise of religion.

Of course, the real problem in the Sherbert case, which the Court did not address, was that South Carolina’s law prohibiting activity on Sundays violates line #3 by imposing one version of Christianity’s beliefs on all of its citizens.

Regardless, RFRA reinstated the Sherbert test. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that RFRA intruded on state’s authority and is applicable only to federal laws, not state laws. Since that ruling, 21 states have passed their own RFRA-like laws, some with important variations on the details of the test.

Weaponizing RFRA

RFRA was passed with overwhelming support by politicians, religious leaders, and advocacy organizations across the political spectrum. Organizations that have long fought for freedom of religion and separation of church and state, including Americans United for Separation of Church and State and the American Civil Liberties Union, supported passage of RFRA. As far as I know, its many supporters genuinely believed that it was a good bill to protect religious freedom.

In the almost thirty years since it was passed, however, RFRA has been morphed from a shield to protect religious freedom into a weapon being used to impose a narrow view of Christianity on the rest of us. As Seidel describes in his book and we will discuss in a future newsletter, this has been done through a strategically-planned, well-funded, two-pronged effort:

Change the composition of the Supreme Court to have a majority of conservative Christians who want their religious beliefs to rule the land.

Bring to the Court carefully selected cases designed to impose the religious beliefs of conservative Christians on the rest of us.

For obvious reasons, Seidel calls the people and organizations behind this effort “Crusaders”. I will adopt his term. I will discuss some of the people and organizations that comprise the Crusaders in the next newsletter.

I’ll turn now to a few of the important cases that have weaponized RFRA.

Hobby Lobby: Blurring Line #2

At its heart, RFRA privileges religion — all other things being equal the government must give preference to religion unless there is a compelling interest to do otherwise. And, being a law instead of being in the Constitution, it is easier to interpret and change than something like the First Amendment.

Background

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires large employers to provide health insurance to their employees and those plans are required to cover essential healthcare needs. Contraception is included among the healthcare services to be provided2 under the ACA. Churches and other religious groups were exempted from this requirement.

Moreover, any employer that did not want to provide health insurance to the employees could instead pay a tax to partially offset the cost of the government providing insurance to the employees. Indeed, the tax was significantly lower than the cost of providing acceptable insurance. If, on the other hand, the employer provided health insurance that did not meet the coverage requirements, a substantially higher tax applied.

Bottom line: No company was forced to do anything, other than to pay a tax. Of course, failing to provide insurance might put the company at a competitive disadvantage in attracting the skilled employees they needed.

The Crusaders filed over 100 lawsuits against the inclusion of contraceptive coverage in the required insurance. These were ultimately consolidated into a single case before the Supreme Court called Hobby Lobby v. Burwell, which involved two companies — Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialities Corporation; Sylvia Burrell was Secretary of Health and Human Services at the time in the Obama administration.

The Subterfuge: Corporations Have Religious Beliefs

Both companies claimed that being required to supply contraceptive services to their employees violated their religious beliefs, which prohibited use of contraception. Whose religious beliefs? Why, the corporations’ religious beliefs.

The claim that corporations have religious beliefs that can be violated is unprecedented and remarkable.

Corporations are legal entities designed to, among other purposes, protect their owners from liabilities associated with the business. When a corporation loses a lawsuit or is convicted of a crime, the owners of the corporation are protected from direct personal consequences (e.g., incarceration). This separation is the raison d'être for corporations.

Justice Alito, writing for the majority, argued that since RFRA protects nonprofit corporations, that it must likewise protect for-profit corporations. Justice Ginsburg, writing for the dissenters (p. 16), explains:

Indeed, until today, religious exemptions had never been extended to any entity operating in “the commercial, profit-making world.”

The reason why is hardly obscure. Religious organizations exist to foster the interests of persons subscribing to the same religious faith. Not so of for-profit corporations. Workers who sustain the operations of those corporations commonly are not drawn from one religious community. Indeed, by law, no religion-based criterion can restrict the work force of for-profit corporations.

Justice Alito’s opinion creates a whole new line of thinking, namely, that for-profit corporations can have religious beliefs, which are entitled to protection.

The Crusaders careful choice of plaintiffs helped justify Justice Alito’s creation. Hobby Lobby is a closely-held corporation controlled completely by David Green, his wife Barbara Green, and their three adult children. Green is among the 100 richest Americans, worth over $4 billion. He and his children wield their money in multiple activities promoting their brand of fundamentalist Christianity.

Justice Alito, writing for the Court’s opinion (p. 18), says:

As we will show, Congress provided protection for people like the Hahns3 and Greens by employing a familiar legal fiction: It included corporations within RFRA’s definition of “persons.” But it is important to keep in mind that the purpose of this fiction is to provide protection for human beings. … And protecting the free-exercise rights of corporations like Hobby Lobby, Conestoga, and Mardel4 protects the religious liberty of the humans who own and control those companies.

Who Protects the People?

Who protects the 13,0005 people who work for Hobby Lobby?

This is where the Court's decision crosses Line #2: It converts RFRA into a weapon that a few people, who happen to be billionaires that control a large, for-profit corporation, can use to impose their religious beliefs on many other people.

Justice Ginsberg further explains (p. 23):

Importantly, the decisions whether to claim benefits under the plans are made not by Hobby Lobby or Conestoga, but by the covered employees and dependents, in consultation with their health care providers. Should an employee of Hobby Lobby or Conestoga share the religious beliefs of the Greens and Hahns, she is of course under no compulsion to use the contraceptives in question. But “[n]o individual decision by an employee and her physician—be it to use contraception, treat an infection, or have a hip replaced—is in any meaningful sense [her employer’s] decision or action.”

Remember that Hobby Lobby and Conestoga could have avoided the whole situation by paying a tax that would have cost less than providing health care. Rather than sidestep the whole issue (and save money at the same time), the Greens and the Hahns sought to impose their beliefs on the choices that their employees were entitled to make in consultation with their health care providers.

The Court’s decision has granted them the right to use RFRA to do exactly that.

The Court

It is perhaps impolitic to talk about the five justices who voted to allow closely-held corporations (closely-held being not well-defined) to both have a religious belief and to impose it on others. But it is important to understand what is happening to the makeup of the Court.

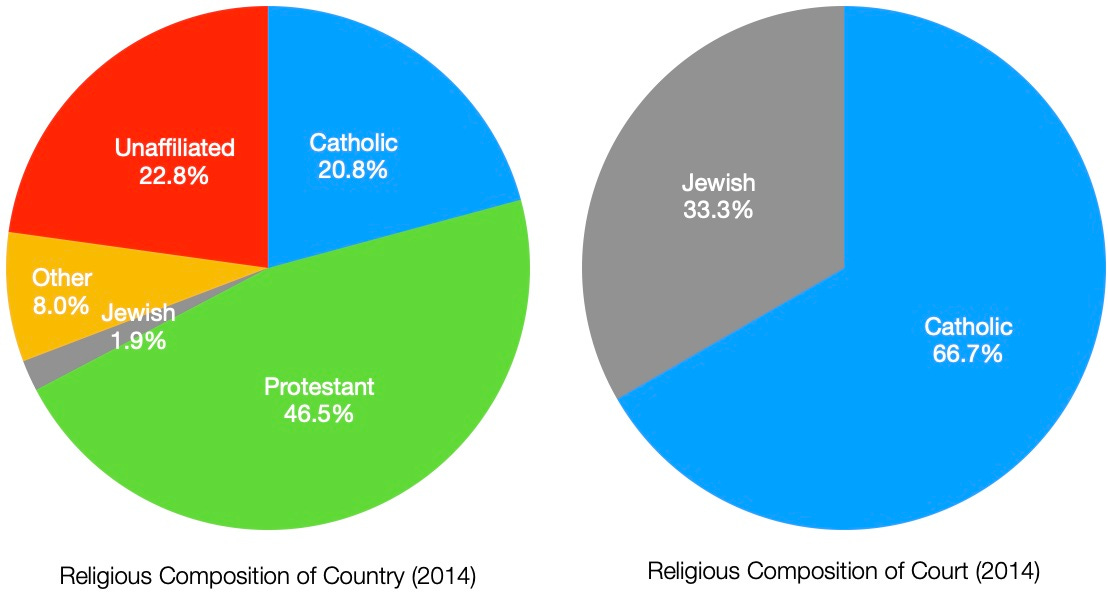

This decision was handed down in 2014. The justices who voted in the majority were five Catholic men (Alito, Kennedy, Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas); the justices who voted in the minority were two Jewish women (Ginsburg and Kagan), a Catholic woman (Sotomayor), and a Jewish man (Breyer).

Besides the obvious discrepancy between the country’s and the Court’s gender distribution, the religious distribution of the Court in 2014 is strikingly out of kilter with the religious distribution of the country:

We’ll see how this happened and how this evolves as we discuss more recent cases in future newsletters.

An Attempted Win-Win Fails

The framers of the ACA knew that coverage of contraception would be controversial among some religious organizations. So, the ACA exempted religious organizations like churches from the requirement to provide contraceptive health care coverage. But since such an exemption imposes the religion’s beliefs on birth control on their employees, who may have other beliefs, a win-win solution was incorporated into the bill.

The ACA requires insurance companies to cover contraceptive services for employees of religious organizations at no cost to the religious organization. The government reimburses the insurance company for the cost of providing such coverage. In this way, the religious organization is neither providing nor funding contraceptive services. Clever.

For this to work, both the insurance company and the government need to know whether or not the religious organization is taking this exemption. The government requested religious employers to fill out a three-line form so that the government and insurance company could provide the benefit.

Remarkably, many religious organizations, including the University of Notre Dame and the Little Sisters of the Poor, filed lawsuits against even this requirement, as a violation of their religious freedom because it imposes a “substantial burden” on them, thus violating RFRA.

Check out the burdensome form6 (it won't take you long):

As US Solicitor General Donald Verrilli put it (p. I), the question to be answered in these cases is “whether RFRA entitles petitioners not only to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage themselves, but also to prevent the government from arranging for third parties to provide separate coverage to the affected women.”

Even this sensible effort to find a win-win, which imposes no real burden on a religious organization’s religious freedom, while providing important healthcare services to which all employees are entitled by law, fails because the real goal of the Crusaders is to impose their beliefs on others.

Once again, RFRA has been used as a weapon.

Trump’s Principles of Religious Liberty

In 2017, the Trump administration issued new "principles of religious liberty" that set out an even more extreme interpretation of RFRA. The document lists 20 principles, including several that expand the scope of RFRA.

One of them makes clear that “freedom of religion extends to persons and organizations”, which is then emphasized by another principle that “RFRA’s protection extends not just to individuals, but also to organizations, associations, and at least some for-profit corporations.”

Another principle says that “Americans do not give up their freedom of religion by participating in the marketplace, partaking of the public square, or interacting with government.” Sounds innocuous, right?

Nope. This interpretation has been used, for example, to allow Christian social service agencies that receive government funding for foster care and adoption programs to refuse participation by people that don’t meet the agencies’ religious criteria. One federally-funded agency in South Carolina, for example, was allowed to discriminate against Catholic, Jewish, and same-sex couples, who would not sign an evangelical Protestant statement of faith.

More broadly, the guidance says that “RFRA too might require an exemption or accommodation for religious organizations from anti-discrimination laws.” Of course, this makes sense for hiring someone like a minister. But the guidance goes on to say “even as applied to employees in programs that must, by law, refrain from specifically religious activities.”

A Win-Win Approach to Fixing RFRA

The Do No Harm Act, which was introduced into the House and Senate in 2021, takes a simple, direct approach. A concise summary of the background and the law, along with a list of supporting organizations, is available here.

The Do No Harm Act amends RFRA to specifically exclude RFRA from being used to:

Undermine nondiscrimination laws

Deny access to healthcare

Evade child labor laws

Thwart laws that protect worker’s rights

Refuse to provide government-funded services under a contract or grant

Refuse to perform duties as a government employee

The win-win is that it preserves all other uses of RFRA, as originally intended when RFRA was passed. It de-weaponizes RFRA but still protects religious freedom.

Although the Do No Harm Act is supported by many organizations, its co-sponsors in the House and Senate are all Democrats. It is currently in committee in both chambers.

What’s Next

We’ve looked at a few of the many efforts to change the meaning of religious freedom — and especially RFRA — to allow people to impose their religious beliefs on others. In particular, we’ve looked at examples of redefining religious freedom to blur Line #2.

We’ll continue next time with examples of blurring Line #3, which is keeping government and religion separate. We’ll also start to look at who the Crusaders are, and how they have successfully worked to change the composition of the Supreme Court, to select and fund cases to be brought in front of the Court, and to shape the public’s perception of those cases using misleading (and false) narratives.

During Prohibition, in the 1920’s, Congress passed the Volstead act, which exempted wine used for religious purposes from Prohibition.

Shockingly, contraception was not included among the original services to be covered by ACA-mandated health insurance. It was added in response to an amendment to the ACA authored by Senator Barbara Mikulski.

The Hahn family controls Conestoga Wood Specialties, a for-profit corporation whose similar claims to those of Hobby Lobby were consolidated into the Hobby Lobby case.

Mardel is a for-profit corporation owned by one of Green’s sons.

The text of the Court’s opinion gives this figure. Other sources say 21,000 people. The difference is not material to the discussion.

I have been a member of Americans United, that deals in 1st amendment religious cases, for years. They particularly defend the freedom from other peoples religion. In general, our constitutional rights are not total and absolute, they are limited by infringing on other folks rights. In general, the strategy of the Christian Right, is to move or eliminate that boundary where someone else’s freedom of, or from religion would be a constraint. The poorly selected SC is all too often on the side of Christian nationalists, trying to push their religious beliefs on others. This is the crux of the wesponization.

In my naive perspective, something that the courts ought to recognize is that some aspects of religion are "practiced at home or in the place of worship (if any)", and some are practiced in public spaces where they affect other folks.

In the former case, government should probably not intrude unless someone's faith requires ritualistic cannibalism of their own family members. Or something similarly extreme that harms individuals (even if it harms other believers).

In the latter case, the courts probably should weigh whether it is necessary, not just approved by a majority, for one person to practice their faith in a way that directly harms anyone or infringes upon anyone else's religious freedom.

In this case, Thuggee behavior of robbing and murdering travelers is not OK, even if that is a fundamental tenet of worshipping Kali. But wearing a yarmulke in public is fine, because it harms nobody and doesn't restrict anyone else's ability to pursue their faith.