Thinking About AI: Part VI - Managing the Impact

We continue our series on AI, focusing on how we might manage AI's impact on our society.

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

As we’ve discussed previously, AI is impacting society for better and worse, a process that will continue and probably accelerate. We, as a society, must decide if and how to manage those impacts. My thinking on this subject derives from six core beliefs.

Core Beliefs

1. There Is No Stopping or Slowing AI

Proposals to impose regulations that slow or stop the development of AI are naïve and will not succeed.

AI is the “next big thing,” the Internet of the 2020’s. The CEOs of the dominant technology companies have already shifted huge investments to AI and we see aggressive competition unfolding in real time. Investors are throwing money at AI startups and less-dominant large companies (e.g., IBM) are looking at AI as a next-wave opportunity.

Congress can barely get out of its own way and is unlikely to mount a serious “slow/stop AI” effort. Lobbyists and PACs would be out in force to either oppose or shape to their advantage any such effort.

More importantly, AI is viewed as so critical to both defense and economic growth that the if-we-don’t-do-it-the-Chinese-will argument will hold sway.

2. Technology Diffusion Dynamics Apply to AI

AI technology will diffuse into society pretty much like other highly-impactful technologies have — slowly.

Probably the most significant modern technology diffusion was replacing human and animal power by first steam engines, then internal combustion engines, and eventually electricity delivered over a transmission network. Depending on how one counts, this took around 150 years.

It took computing technology more than 40 years to become a major part of our personal and economic lives.

AI’s impact may happen more rapidly, but we are still talking decades not years.

3. AI Is a Tool

AI is a tool that makes it easier and faster to accomplish certain tasks, increasing economic productivity and affecting the work that humans do and the products and services that corporations produce.

We’ve seen this with other tools and can expect the same sorts of effects:

AI will eliminate some jobs and destroy some individuals’ careers.

AI will create new jobs and career opportunities, probably increasing overall economic growth.

AI will destroy some companies and professions.

AI will be the basis for new companies and professions.

Ultimately, AI will increase economic activity, but many people and companies will be hurt during the transition.

AI-based tools will help other people in their existing professions. For example, I know coders who already use ChatGPT to draft first versions of code, saving them time but not (yet?) eliminating their work.

There’s some evidence that AI-based image and pattern analysis could help significantly with medical diagnosis, improving both speed and accuracy.

4. AI Will Exacerbate Existing Societal Problems

AI is a force multiplier for people and organizations that want to spread disinformation or perpetrate scams. We’ve seen examples before. AI didn’t create disinformation or scams, but will exacerbate both, increasing the likelihood that our democracy will fail to survive.

Similarly, AI will worsen income and wealth inequality because its powers will be most available to people and organizations with access to the skilled people and the massive computing resources needed to train and deploy AI systems.

And, of course, as AI disrupts people’s livelihoods, there are going to be additional people — including families — needing help.

5. AI’s “Thinking Ability” is Mostly Hype

As impressive as they are, today’s AI’s don’t understand and don’t think logically.

There is a substantial possibility that leaders in business and government will be sufficiently disappointed with their experiences trying to use AI that the vast, broad impact expected of AI will not come to fruition.

This is a longer discussion, which I’ll delve into below. In the meantime, you might recall the examples I gave previously here and here.

6. Our Intellectual Property and Personal Responsibility Laws are Inadequate for AI

When ChatGPT defames someone (see here), who is liable? Is anyone liable? When an AI “writes” prose or music or “creates” art, can those works be copyrighted? If so, who owns the copyright — the company that created the AI or the person who crafted the prompts to the AI that resulted in the work?

When an author’s work is plagiarized by ChatGPT or an artist’s drawing is incorporated without permission into a generated image, is the artist due compensation? Procedurally, how would this work?

When an AI summarizes an article published online without sending the reader to the online publication, is the article’s publisher entitled to compensation in lieu of the advertising revenue that the publisher ordinarily receives when someone reads the article?

When a “conversation” with an AI chatbot sends an unstable or depressed person into suicide, who is responsible?

You can no doubt think of many similar questions.

Defending Against Disinformation

Disinformation purveyors are going to love AI. AI will make producing disinformation less labor intensive, cheaper to produce, and probably more effective.

Low-Tech Disinformation

But here’s the thing: Disinformation is already a huge threat to democracy around the world. It is spread via all sorts of media at all levels of politics.

Low-tech disinformation is effective. For example, in the 2022 election for the NC House in a district near where I live, Ricky Hurtado, a Democratic incumbent, made the mistake of volunteering to do cleanup work in a local park. He was photographed and here’s what his Republican opponent and his allies did:

Hurtado lost the close election. The Charlotte Observer’s opinion piece A new level of dishonesty: Mailers targeting NC Democrats photoshop the truth says that “[m]ailers recently distributed in several competitive North Carolina House districts feature deceptively edited photos of Democratic candidates, tying them to the ‘defund the police’ movement and Black Lives Matter protests.”

AI Forces Fighting Disinformation Broadly

Disinformation is spread on television, YouTube, social media, newspapers, magazines, books, political mailings, billboards, etc. AI will make it worse (or, better, if you’re in favor of using disinformation in politics and business).

Other than making it cheap to create and spew ever-increasing flows of disinformation, AI doesn’t fundamentally change the problem that we already have.

Here’s the positive spin on it: Perhaps the advent of AI will make it so much worse that we finally fight disinformation — all of it — not just AI-assisted disinformation.

Fighting Disinformation

Certain kinds of disinformation are protected by our free speech laws. If a politician (or an organization) wants to say that violent crime is rising across the nation so you should be very afraid, that the crime is caused by rapists streaming into the country from Mexico, that you need guns to protect yourself and your family, and that the Democrats are coming to take your guns away, the politician can do that. The politician can say it out loud on TV or insinuate it anonymously through media. Regardless, there’s no accountability for the lies.

Take it further, and intentionally and knowingly defame a particular person and cause harm to that person, then there is recourse through defamation laws. Realistically, accountability through defamation and libel laws is slow, impossibly expensive for most people, and fraught with risks.

E. Jean Carroll might have been able to hold Donald Trump accountable for defaming her (we’ll see how the delays and appeals will go) and Dominion Voting Systems somewhat held Fox News Corporation accountable for defaming them, but certainly the Ricky Hurtado’s of politics can’t do so. And lawsuits that take years can’t undo the effect of defamation on the outcome of an election.

I don’t see a legal solution to this situation.

This is a cultural issue, where it has now become acceptable for major players in our political combat to fully take off the gloves. Until the leaders of all political parties set the right examples, this situation will persist.

Section 230 and Online Disinformation

In the “good ol’ days” of broadcast TV and radio, the Federal Communications Commission’s Fairness Doctrine required broadcasters to tackle controversial topics of public interest and to do so in a way that reflected multiple viewpoints. The Fairness Doctrine was repealed in 1987, quickly giving rise to talk radio hosted by disinformation spreaders like Rush Limbaugh. Broadcasters were no longer obligated to present contrasting viewpoints.

As a non-broadcast service, cable TV was never subject to the Fairness Doctrine.

Along came the World Wide Web in the 1990s. Congress passed Section 230 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, granting “interactive computer services” immunity from liabilities arising from providing a platform for third-party content providers. In other words, Facebook or Twitter can not be held liable for the scurrilous lies that your nutty uncle or Donald Trump or anyone else posts on their platform.

Section 230 was seen in the 1990s as necessary to enable the growth of the then-nascent platforms.

Interestingly, Congress saw fit in 1998 to limit Section 230’s ability to protect platform providers from liability for copyright infringement by their third-party content providers. Guess what? Facebook, Google, and the like actually police their platforms for copyright infringement.

These platforms no longer need protection to grow. They are already the dominant players in their industry.

Congress could, therefore, further limit Section 230’s ability to protect platform providers from liability for publishing false or defamatory third-party content. This would have to be done carefully and certainly would impose costs on the major platform providers.

It would also open them to accusations of bias, a problem they already face because their algorithms for choosing what to display to their users are opaque and not accountable for anything other than raising user engagement — and hence advertising revenue — regardless of impact on society.

Suspend disbelief for a moment because, below, I’ll propose a win-win that combines this idea with what I’m going to discuss next.

Verified Responsible Parties

All social media platforms grapple with the “fake account” problem, accounts that purport to be owned by a particular individual or organization, but, in fact, are not.

Humans, and sometimes robots, operate through fake accounts to sow disinformation or perpetrate scams.

A good solution to this problem is verification of the identity of the accounts’ owners. You’ve probably read about pre-Musk-Twitter’s blue check mark indicating that Twitter has verified the identity of the owner. Pre-Musk, this was limited to well-known people or organizations. As a consumer of information, the blue check mark indicated that you could trust the source. If you read a tweet from NPR and saw the blue check mark you could be sure that you could trust that content (to the extent that you trust NPR).

But Musk destroyed this approach for Twitter by converting the blue check marks into an $8/month revenue stream rather than a real verification.

Facebook has a verification feature, too, which allows “notable” people or organizations/brands to establish who they are. Once verified, their posts get a verified check mark.

Now, imagine the next steps:

All social media would offer verified responsible party indicators to all people and organizations. Being “notable” would no longer be required to be eligible for being verified. But verification would require proving identity and the account profile would be required to be listed in the verified name. (I’ve previously discussed in a related context some ideas for how to do verification and how to pay for it. Technology has marched on since I wrote that, so other approaches should be considered too.)

All users of a social media platform could specify that they only want to see content from verified accounts. This should be the default. That way, users would not see the disinformation from, for example, Russian agents sowing dissent while purporting to be fellow Americans.

Social media algorithms that decide what content to show would favor content from verified parties.

Suppose we did this. Now, if I want to use AI to generate my posts, that’s fine, but I will be personally accountable for their content. Likewise for corporations and other organizations.

Now, go one step further: If we limit Section 230’s ability to protect platform providers from liability for the the third-party content they publish, this would motivate platform providers to implement verification as a means to reduce the platform’s liability risks.

Win-Win Proposal

In a nutshell, my win-win proposal for controlling online disinformation is:

The advent of AI makes solving our online disinformation problem more important and urgent.

Treat online disinformation as one problem, not as an AI-specific problem.

Amend Section 230 as follows:

Make “large” online providers liable for third party content that they publish.

Provide a safe harbor1 for online providers exempting them from liability for content from verified parties.

The win-win is that society benefits from better control of online disinformation and the social media platforms remain protected from liability as long as they take the necessary steps to broadly implement verification.

Helping Displaced Workers

There is a lot of (justified) discussion about the harm AI could cause to individuals as their jobs and career paths are affected by deployment of AI in many businesses. We live in a capitalist society in which, for better or worse, the pursuit of profit is the fundamental driving force in our economic system.

In this system, attempts to slow change to limit impact on workers generally fail. AI, as a new technology, will be no different. Perhaps its pace will be faster than the diffusion of other impactful technology, but even that’s not certain.

History would say that we can not and should not attempt to slow down AI-based impact on jobs. If we artificially slow AI deployment as a tool in business, then our businesses will be at a significant disadvantage compared to their competitors in countries that choose not to slow AI deployment.

If we shouldn’t slow the deployment of AI, how do we reduce harm to individuals’ livelihoods?

We help people directly. We learned during the darkest days of the Covid pandemic that significantly enhanced unemployment benefits can make a huge difference in people’s lives. If AI drives a big downturn in jobs we should generously use benefits to help people get through it.

We should not require people to prove that AI was why they lost their job: The connection between AI deployment and losing a specific person’s job will be nebulous and impossible to prove.

We can, however, monitor the deployment of AI, the change in jobs and wages, and the growth in corporate profits and GDP that results. We would pay for enhanced benefits out of the growth in GDP and corporate profits.

Enhancing benefits will be controversial. There will be the laziness scolds and the debt scolds. And, yes, there will be waste.

But, if AI makes its predicted big impact, there will be hungry and angry people who will need society’s help. Beyond human decency, we must help them to avoid destroying our already fragile democracy. We’ve shown during Covid that, however flawed, we can create enhanced benefits that help real people without harming the economy.

Additionally, relevant job training opportunities should be well funded.

Reducing Concentration of Wealth & Power

In their new book, Power and Progress: Our 1000-Year Struggle Over Technology & Prosperity, released just this week2, MIT economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson review the long history of the struggle over whether and how to share the benefits of new technologies. History suggests that the benefits of new technologies are not shared broadly until something forces a change.

In Chapter 11, they articulate a “critical formula necessary for escaping our current predicament”, by which they mean (p. 447) “the enormous economic, political, and social power of corporations, especially in the tech industry.”

They go on to say (p. 453):

“The concentrated power of business undercuts shared prosperity because it limits the sharing of gains from technological change. But its most pernicious impact is via the direction of technology, which is moving excessively toward automation, surveillance, data collection, and advertising. To regain shared prosperity, we must redirect technology, and this means activating a version of the same approach that worked more than a century ago for the Progressives.”

The formula is three-fold:

“Altering the narrative and changing norms.” Citizens need to develop an informed view of what is troubling the country economically, not “just accepting the line coming from lawmakers, business tycoons, and the yellow journalists allied with them.”

“Cultivating countervailing powers.” Corporate powers must be held in check by broad movements advocating reform, including workers’ unions and aggressive enforcement of anti-trust laws.

Policy solutions. For example, as we’ve discussed in prior newsletter issues, our tax system is highly skewed to reward capital over labor. Policies that allow accumulation of massive wealth and its concomitant power must be changed.

AI is yet another technology in a long list of technologies that have changed the world. In most respects, the lessons learned from the introduction of those other technologies hold today.

Starting with the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s, we’ve allowed a dramatic shift of wealth and power to the few at the expense of the many, as we’ve discussed previously many times (see https://winwindemocracy.org/t/wealth). Despite a lot of talk, Congress and our political leaders have been unwilling or unable to make any progress on this concentration of wealth and power; indeed, they’ve changed the tax system to further concentrate wealth.

AI will accelerate the already egregious concentration of wealth and power. But it is still the same old problem.

The question is whether the effects of AI will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back, driving us to finally pay attention and start the decades-long effort to defeat our modern Gilded Age by “altering the narrative and changing norms” and ushering in a modern version of the Progressive Era of the early 1920s.

Devaluing Creativity

I mentioned earlier that AI raises intellectual property issues that current law (understandably) didn’t anticipate. I could easily write a whole newsletter issue on just that topic. I will avoid the temptation to do that; instead I refer you to the article The scary truth about AI copyright is nobody knows what will happen next, which appeared late last year in The Verge. It provides a good overview easily understood by non-lawyers.

Copyright and Fair Use

That said, I want to discuss one important topic here. United States copyright is authorized directly in the Constitution’s Section 8, the enumerated powers of Congress section:

“[The United States Congress shall have power] to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

The purpose is clear: “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts”. It does not say “to protect the livelihood of authors and artists and inventors.” But if such creators can’t earn a living, such work is not going to be produced.

In the struggle to balance the public’s need to benefit from “the Progress of Science and useful Arts” with the creators’ needs to earn a living, copyright law has evolved the concept of fair use. A fair use of a work is not an infringement of copyright law, and the creator can not sue for compensation or control.

The Copyright Act of 1976 dictates, based on prior court decisions, that

“In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.”

There have been many court cases that have shaped and continue to shape the practical meaning of these four factors.

An Example

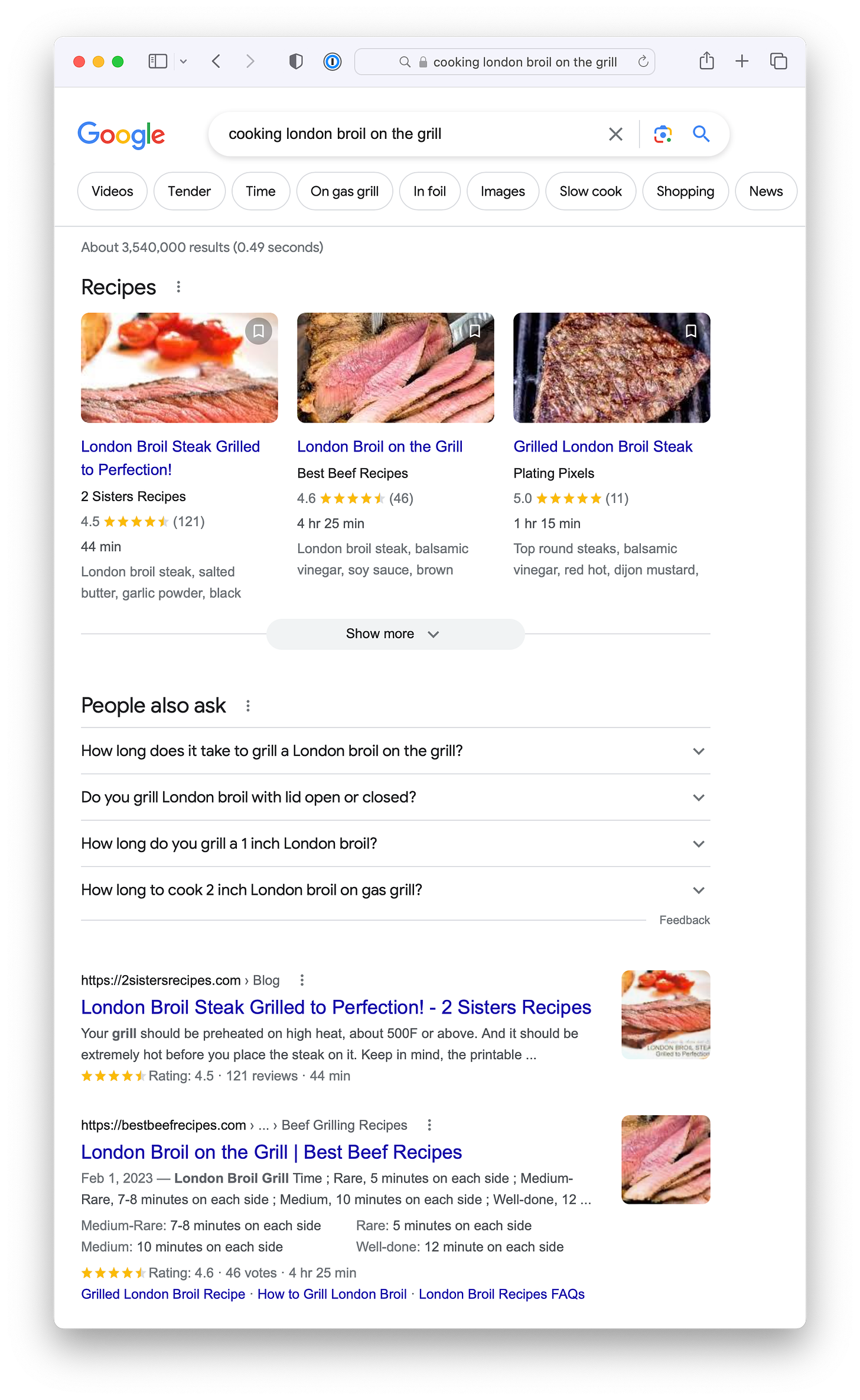

I do the grilling in our family. I want to know how to grill London broil.

Asking Google yields:

To see a recipe, I choose one of the articles offered, click on the link, and head over to the web page.

My visit to the web page might be monetized in various ways, such as advertising, affiliate links to vendors3, or simply by boosting the author's reputation or the site’s standing in searches. Regardless of the mechanism, the page’s author and/or publisher benefits from my visit.

Now, look what happens when I ask the same query of new Bing (which uses some combination of conventional search and GPT-based AI):

At the bottom, you can see the steps of the recipe and scroll through them. No need for me to visit the website at all. Unless Microsoft has made some agreement with the website’s owner, the website and the recipe author have no opportunity to monetize my use of the information on the page.

It gets worse directly using ChatGPT:

Seems like a great recipe. I have no idea where this came from. Is it from a famous chef or from ChatGPT’s synthesis of a recipe from among the many it has “read”? I couldn’t visit the web site even if I wanted to. Whoever provided this recipe (or parts of it) has no opportunity to monetize their work.

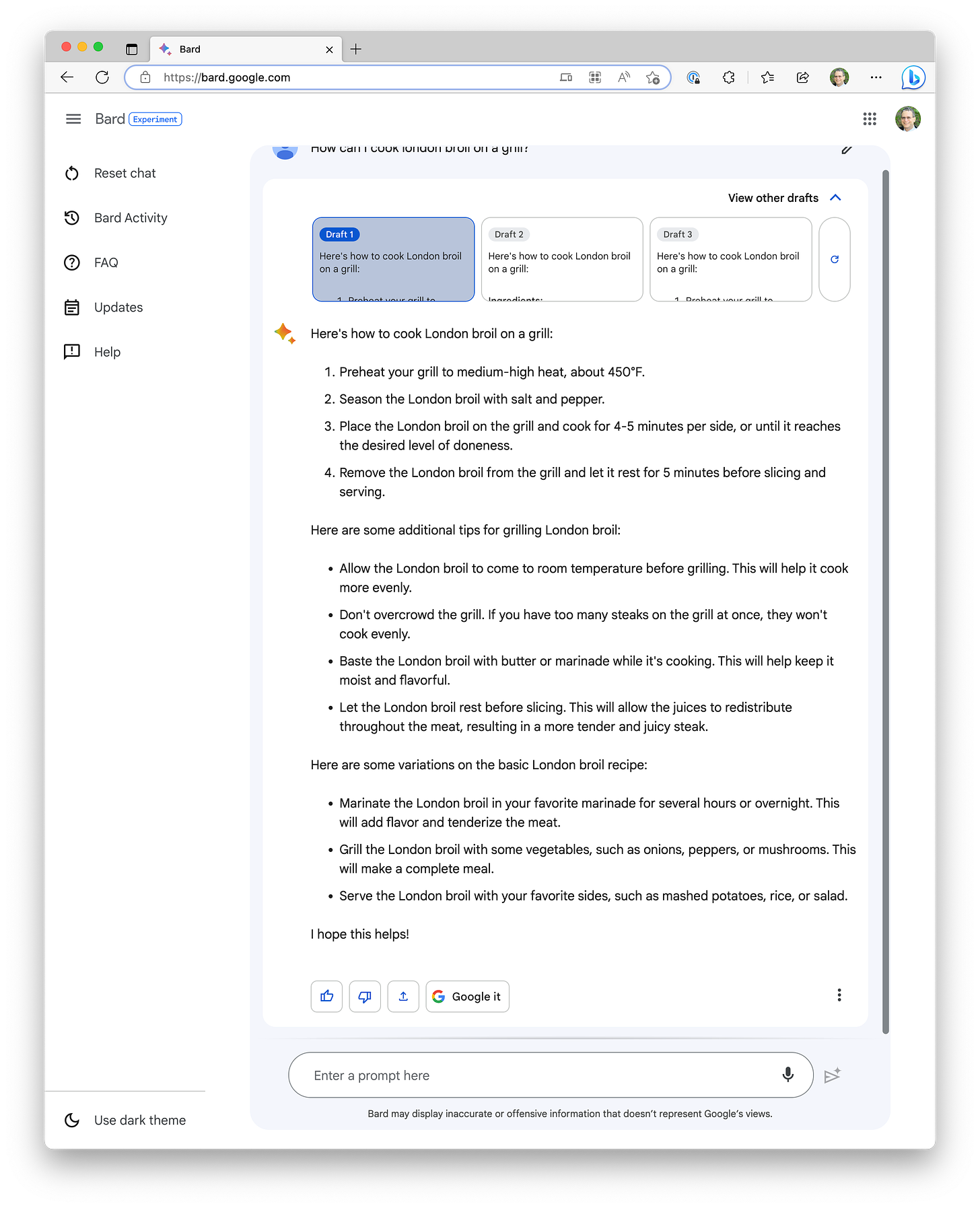

Likewise, Google’s Bard yields:

It gives me “drafts” of three recipes from which to choose, again with no way for the authors of these recipes to monetize their work.

Is this “fair use” of the intellectual property of the people who provided the web sites from which ChatGPT (and, hence, new Bing) and Bard came up with recipes? It wouldn’t seem so given consideration of the fourth factor of the fair use law.

Killing the Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs

AI’s that suck up information and ideas from the existing content on the Web, summarize it for easy consumption or use it to synthesize derivative content, might very well destroy future creativity be killing the incentive for people to create new content. A reader of this newsletter has told me that he is seeing a decrease in visitors to his website, which he attributes to this phenomenon.

Devaluing creative work is, in my mind, one of the top risks of AI as it is currently being deployed. AI is already good enough to have massive impact on the ability to monetize new works.

I don’t have a solution to propose, but I think that this problem is not discussed enough. It is an urgent problem. Think back to the near-death of the music industry and the threat to musicians’ livings when digital music came into being.

Does AI Think? Does AI Understand?

Inevitably, in discussions about AI among my friends, these two questions are front and center, either explicitly or as an implicit assumption that AI technology can think and understand. We’ve discussed this in earlier newsletter issues, but I’m raising it again here because I think most people still don’t really understand this important issue.

AI’s based on large language models (i.e., GPT-like systems) have an amazing facility with language. But we humans are gullible. Because ChatGPT can generate reasonable — even excellent — responses to our prompts, we are naturally inclined to believe that the AI understands and thinks. Remember the shocking reaction to ELIZA/DOCTOR in the 1960s that we discussed previously?

So, do they think and understand? Not really. In previous newsletters, we’ve seen many examples where the responses to prompts are well-written, with a confident tone (or, even another tone if requested), but factually nonsense — what industry jargon calls hallucination. Note the anthropomorphism. Yet another reason we are gullible.

We’ve also seen an example in which ChatGPT is unable to solve middle-school level word problems.

Here’s another simple example:

Prompt: how many integers are there?

Response: The set of integers is infinite. There is no limit to the number of integers because you can always find another integer by adding or subtracting 1 from an existing integer. In mathematical notation, the set of integers is denoted by the symbol Z and it includes all positive and negative whole numbers, as well as zero (0). So, while there isn't a specific count of how many integers there are, we can say that the set of integers is infinite.

This response was fine, if overly long. From this response, you’d think that ChatGPT “understands” integers and the concept of countably infinite sets.

So, let’s follow up (in the same chat session) on that “understanding”:

Prompt: What are the ten largest even numbers?

Response: The ten largest even numbers are as follows:1. 10,000,000,000

2. 9,999,999,998

3. 9,999,999,996

4. 9,999,999,994

5. 9,999,999,992

6. 9,999,999,990

7. 9,999,999,988

8. 9,999,999,986

9. 9,999,999,984

10. 9,999,999,982These numbers are in descending order, starting from the largest even number, which is 10,000,000,000, and continuing with each subsequent even number.

This response is utter rubbish. It shows that ChatGPT doesn’t understand at all.

And, just to be sure that this isn’t a ChatGPT idiosyncrasy, I tried the same prompts with Bard. It produced a different but also good response to the first prompt, and a different but also utter rubbish response to the second prompt.

Don’t conclude that a well-written response to a prompt indicates “understanding” or “thinking”.

This is particularly important to keep in mind as you evaluate for yourself various predictions and claims about how AI is going to affect our future.

What’s Next?

I plan that the final (at least for now) topic in this series of posts on AI is regulation. I am particularly concerned about the calls from the industry for government regulation.

Despite the nice words written and spoken, I’m skeptical that those calls for regulation are for the benefit of society. Rather, I have the admittedly cynical view that the requests by the industry for regulation are more about establishing safe harbors for what they want to do than about imposing meaningful limits on what they actually do: With suitable regulations in place, when something bad happens as a result of their technology, the response will be “it [the something bad] is really unfortunate, but we complied with all of the federal regulations”.

But first … there is another threat to democracy that concerns me even more than AI concerns me. I will address that in the next newsletter issue, then return to complete the AI series.

Until next time …

A safe harbor is a feature of a law that deems certain conduct acceptable for the purpose of that law.

Here’s an example from personal income taxes: Our income tax system is pay as you go. If you receive a salary, income tax is withheld from every paycheck. But, if you receive your income irregularly, you must file quarterly estimated income tax returns, which update your estimate of your annual income and pay the estimated taxes for that quarter. If, at the end of the year, your estimate of your income is wrong, you can owe both penalty and interest.

One safe harbor is that if you pay 100% of your previous year’s tax liabilities in estimated tax payments (110% if you earn high income), you are exempt from penalty and interest.

I have only had opportunity to skim small parts of it and look forward to actually reading it.

Affiliate links pay the owner of a web site a commission when someone makes a purchase through the affiliate link.